On June 5, 1981, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Report (MMWR) published the first report of AIDS, describing five cases of unusual Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) among previously healthy young gay men in Los Angeles.

On July 1, his first day on the job, Paul Volberding, MD, then age 31, saw the first Kaposi sarcoma (KS) patient admitted to San Francisco General Hospital (SFGH). Two days later, a second MMWR report described 10 more cases of PCP among gay men in Los Angeles and San Francisco as well as 26 cases of KS. A follow-up report in August included more than 100 cases.

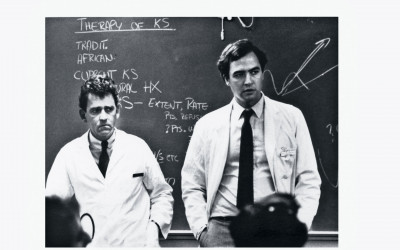

Marcus Conant, MD, and Paul Volberding, MDCourtesy of UCSF Archives & Special Collections

Volberding, a medical oncologist, and Marcus Conant, MD, a dermatologist, soon started the nation’s first KS clinic at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). As a growing number of mostly gay men presented with a range of illnesses linked to immune system collapse, Volberding teamed up with infectious disease specialist Constance Wofsy, MD, Donald Abrams, MD, and others to start the nation’s first HIV outpatient clinic. Ward 86 at SFGH opened on January 1, 1983, followed that summer by the first inpatient AIDS unit, Ward 5B.

Donald Abrams, MD, Constance Wofsy, MD, and Paul Volberding, MDCourtesy of UCSF Archives & Special Collections

Multidisciplinary medical providers collaborated with community organizations to offer a full range of care and services to people with AIDS, many of whom had been rejected by their families of origin and treated badly by the medical establishment.

“I don’t think we ever had a great strategic plan—it was really quite organic,” Volberding tells POZ. “We in the medical community benefited from the information networks that were out there in the gay community. We knew that we couldn’t deliver the at-home services our patients needed, but organizations in the community could. We had our different roles, and we respected each other in those roles.”

Although it was dubbed “the San Francisco model” of HIV care, similar collaborative efforts emerged across the country, especially in other cities with large gay communities. Many of the doctors and researchers who spearheaded the early AIDS response were at the start of their careers, in the same age group as the young people they were seeing with the vexing new disease.

“Those of us who are running these programs are largely products of the ’60s,” Volberding recalls in an interview for the University of California’s San Francisco AIDS Oral History Project. “We were very young, and I think prepared to think outside the usual channels, prepared to do things that weren’t completely kosher, like multidisciplinary programs…. We felt free to redefine ourselves at the drop of a hat.”

The LGBTQ community stepped up to provide services ranging from food delivery to buddy programs to hospice care. Author Larry Kramer and others started the nation’s first AIDS organization, Gay Men’s Health Crisis, in January 1982. A few months later, Volberding, Conant, activist Cleve Jones and others founded the Kaposi’s Sarcoma Research and Education Foundation, which later become the San Francisco AIDS Foundation.

Groups such as Project Inform in San Francisco (started by Martin Delaney and Joseph Brewer in 1985) and the PWA Health Group in New York City (founded by Thomas Hannan, Michael Callen and their doctor, Joseph Sonnabend, MD, in 1987) educated the community about the new disease and helped people with AIDS access experimental and alternative therapies.

People with AIDS and their allies engaged in increasingly militant activism, demanding more government funding for research and services, urging faster development of new treatments, fighting discrimination and defying state laws to start the first needle exchange programs.

As early as 1983, a group took the stage at the National AIDS Forum in Denver, asserting that they were not “victims” or “patients,” but “people with AIDS.” In October 1985, people living with AIDS and what was then called AIDS-related complex (ARC) chained themselves to the doors of the federal building in San Francisco, leading to the ongoing AIDS/ARC Vigil that continued for a decade. The best-known AIDS activist group, ACT UP New York, started in March 1987 and spawned the Treatment Action Group (TAG) in 1992.

The Denver Principles led to lasting changes in the relationship between people living with medical conditions and the health care system. ACT UP’s protests against the Food and Drug Administration and the National Institutes of Health— coupled with insider meetings—resulted in other long-term advances, including new mechanisms for accelerated drug approval.

The combined efforts of researchers, clinicians, public health officials, activists and people living with HIV produced spectacular breakthroughs in prevention and treatment. Today, a single daily pill or monthly injections can prevent HIV and keep the virus under control. And people who start treatment promptly and receive good care can expect to live a normal life span.

But challenges remain. AIDS revealed long-standing disparities in access to care that persist to this day. Gay and bisexual men account for two thirds of new HIV cases, and young men are especially at risk. Black and Latino people, who bear the brunt of the epidemic in the United States, are less likely than whites to use pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and more likely to acquire HIV, but they are less likely to receive adequate care, start antiretroviral treatment and achieve an undetectable viral load. People experiencing homelessness and people who inject drugs are particularly disadvantaged.

On the global level, it took years after the advent of effective combination therapy in the United States and Europe before the drugs reached people living with HIV in low-income countries—and many still do not have access to treatment. And after decades of research, there is still no vaccine for HIV, and a cure remains elusive.

“We knew before HIV that we lived in a desperately unequal country. The disparities in American society were in your face. They thought of us as disposable people,” ACT UP and TAG veteran Gregg Gonsalves, PhD, now an assistant professor of epidemiology at the Yale School of Public Health, tells POZ. “The [2000] Durban AIDS conference was a wake-up call for a lot of people who had not focused on the global epidemic and the stark inequalities in access to drugs. It changed the consciousness of a whole generation of researchers, activists and people living with AIDS in the Global North.”

HIV advocates rally at the 2009 International AIDS ConferenceLiz Highleyman

Today, some of the same people—now senior scientists, veteran clinicians and activist mentors—are leading the response to COVID-19. And some of the same challenges are once again at the forefront. People of color and low-income people have been hit hardest by the new pandemic. And, as we saw with antiretrovirals, the effective vaccines that are pulling the United States out of its epidemic are still not widely available worldwide.

“The two epidemics have a lot to learn from each other,” Volberding says. “I would love to have seen a vaccine for HIV the way we have now for COVID. On the other hand, I’d also love a treatment for COVID that was as effective as the ones we have for HIV.

“Think how far we’ve come with HIV treatment. We can certainly remember the bad days of the epidemic when either we didn’t have anything that worked or we had things that worked but were incredibly toxic,” he continues. “I think we’re sometimes lulled into complacency because of our success. We have one pill once a day or even one injection once every two months. The range of options is growing, and we’re now seeing drugs being developed that might work in completely different ways and offer hope to the people that have become very resistant. Our drugs are available even in some of the most resource-limited settings. We did that because political leaders’ feet were held to the fire. Now we need to do that for the COVID vaccines.”

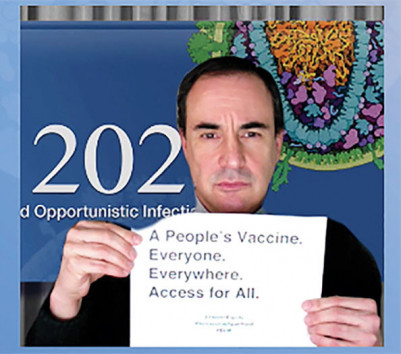

Gregg Gonsalves at CROI 2021CROI 2021 screenshot

Gonsalves is among the many HIV activists and scientists who have turned their attention to COVID-19 vaccine equity. “Now we’re in a sort of 1996 situation, where we have vaccines that work for us, but people around the world are dying for lack of access to them. We’re again seeing the same medical apartheid we screamed about 20 years ago with AIDS drugs,” he says. “In the old days, people could say, ‘Oh, treatment access in Africa is a nice thing, but it doesn’t affect me directly.’ But a raging viral epidemic outside the U.S. that can come back with variants resistant to current vaccines should concern everybody. If we can put a rover on Mars, we can set up a global network of companies that can make enough vaccines to protect the planet from a new pandemic.”