David Morton, the director of Holding Achilles, wants to reclaim the queer aspects of Achilles’ and Patroclus’ relationship in Homer’s Iliad.

It is doubtful that their relationship would have been seen as ‘queer’ by Greeks in the classical period, 1000 years after the Iliad’s setting. Gay love, and non-gendered eros, or love, was the norm by Greek aristocratic men and women. Morton calls the observation “fascinating.”

“Gay relationships were clearly suppressed during the Christian period,” says Morton.

It was in the west that gay love was seen as particular to ancient Greeks, it is doubtful that ancient Greek aristocrats like Achilles, would have thought much about what gender they loved, or slept with.

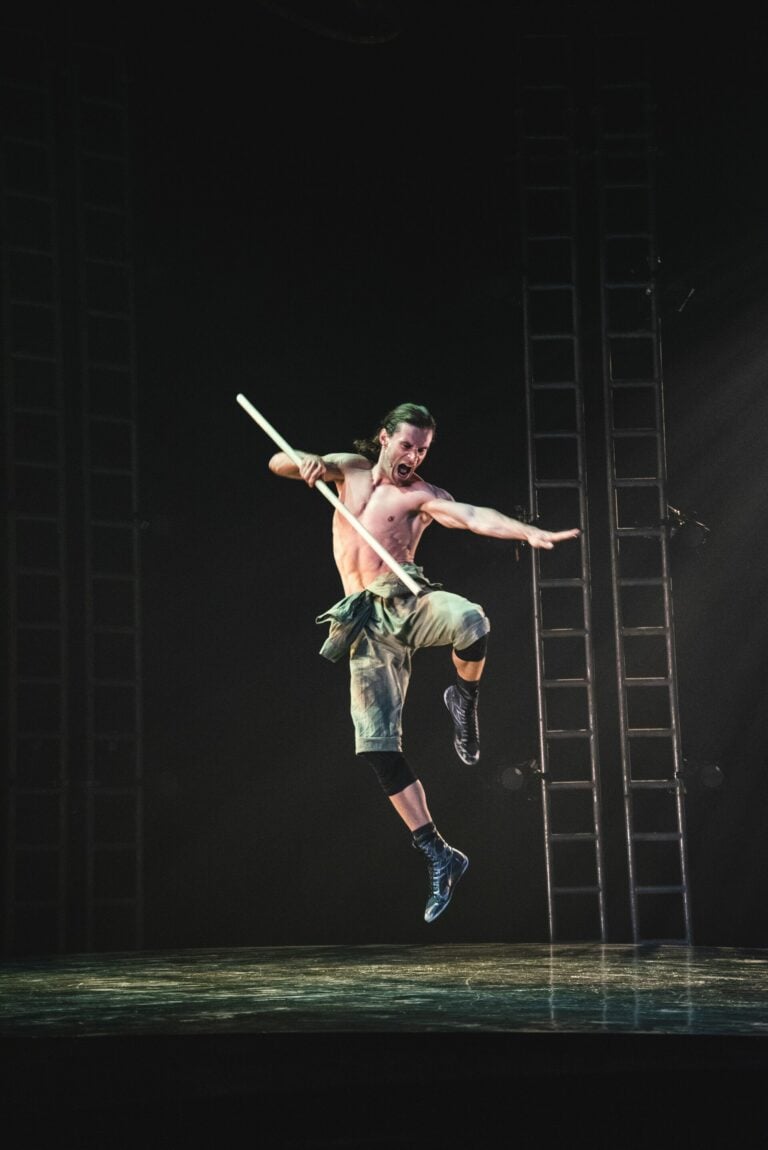

Morton’s production co-opted architects of visual theatre Dead Puppet Society and the masters of physical theatre Legs On The Wall.

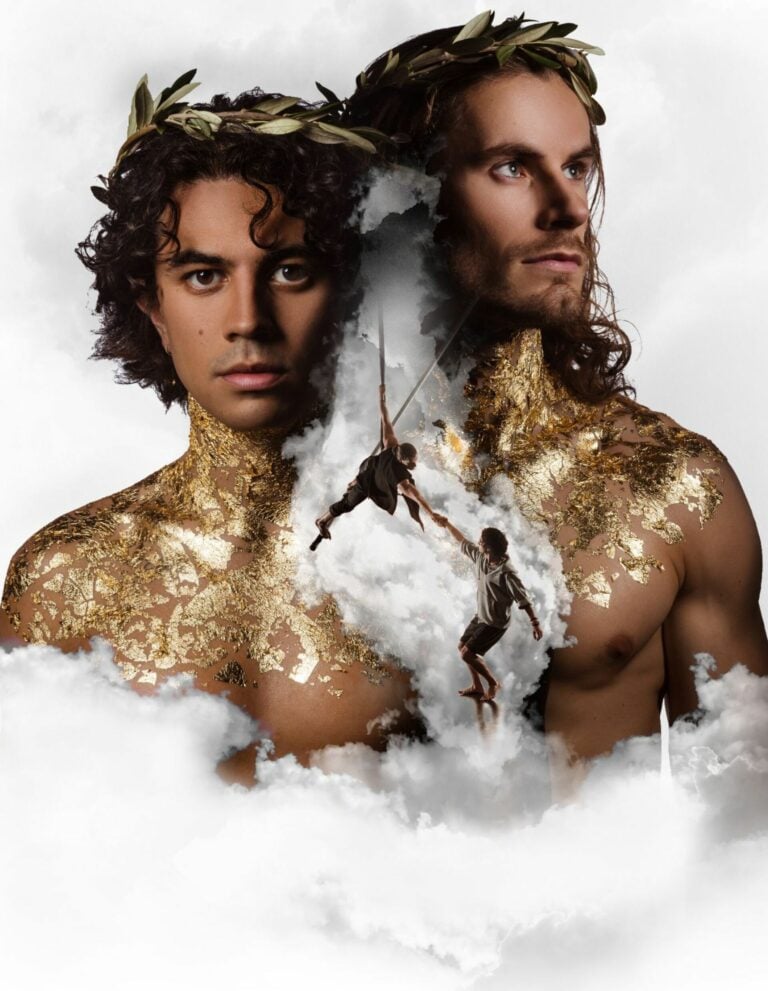

A poignant new score by Tony Buchen and Chris Bear is performed live by Montaigne. Achilles played by Karl Madsen and Patroclus by Karl Richmond have brought a new life into the Homeric classic.

“Tony Buchen and Chris Bear are absolute superstars, and what they created together is breathtakingly good,” says Morton.

“It’s a massive work for us with the bringing together of the Dead Puppets Society and Legs On The Wall. Normally our organisations work independently and make smaller works, this is big, us coming together to make this big festival piece, and we have high hopes.”

In Homer’s Iliad the two heroes never had sex with each other, that idea arose in Plato’s Symposium where aristocrats, including Socrates and his young lover, the strikingly beautiful general, Alcibiades, drink and discuss the essence of Eros, or love.

“I find it most interesting, and one of the reasons why we wanted to tell this story is the Symposium, where this re-framing occurred,” says Morton to Neos Kosmos.

“In different eras it’s been viewed very differently, the relationship between Achilles and Patroclus and the way it’s often viewed as a model for the ideal sort of relationship.

“Achilles’ and Patroclus’ story made me interested in the world we’re living in today in Australia and how this ancient story can be reimagined,” Morton says.

In Morton’s adaptation there are “significant shifts, particularly in the second act, where the idea of heroism, where the strongest, or the best combatant, is the hero.”

“We should turn away from that ideal of heroism and look instead at individuals who are more concerned with the service to others, who find answers through compassion rather than military conflict”, Morton explains.

Yet the most adept and successful warriors, the Spartans, made sexual relations between men a requirement, almost. Spartan women were the freest in Ancient Greece, they pursued martial arts, spoke their minds in the senate, and could have sex with anyone. Any child they bore was Sparta’s, not theirs. Men were taken from mothers at the age of seven and trained as warriors and lived a life in a military camp. Achilles and Patroclus were sort of model for Spartans.

Romans later used Spartans (and Helots) as frontline defence troops, especially in retreat, as they would never leave their lover to die in the field alone.

In Homer’s classic, Achilles’ rage is insatiable, and often the cause of great pain for as many, enemy and friends. Rage was stamped on him since birth; “μῆνιν ἄειδε θεὰ Πηληϊάδεω Ἀχιλῆος, οὐλομένην, ἣ μυρί᾽ Ἀχαιοῖς ἄλγε᾽ ἔθηκε – Rage — Goddess, sing the rage of Peleus’ son Achilles, murderous, doomed, that cost the Achaeans countless losses.”

His mercurial nature, and heightened sense of personal injustice, makes him a complex character. Privileged, yet tragic and forlorn.

Morton says he “wanted to look at heroic sacrifice, to re imagine Homer’s perspective.”

The Iliad was possibly the first great anti-war literary form.

No one comes out clean, the Greeks led by Agamemnon invade the Trojans over a woman, Helen.

The Trojans, a parallel civilisation worshiped the same gods, and in ten years of war the Greeks turn Troy to ashes.

Everyone pays a price for hubris. Achilles to avenge the death of his love Patroclus kills Hector, (son of Trojan king Priam), who killed Patroclus thinking it was Achilles.

Achilles drags Hector’s body behind his chariot to the camp and then sets his corpse around the tomb of Patroclus. Yet, Achilles succumbs to the Trojan king Priam who disguised as a pauper enters the Greeks’ camp to beg for his Hector’s body back.

Horrific and heroic deeds on both sides, Greeks and Trojans. Empathy, caring and love, never totally defeated in the horror of war.

Morton wants to take the work to Sydney, and Melbourne and hopes to show it in London.

Asked if he would consider Athens, now a centre of contemporary performance, especially the reinterpretation of classics Morton was ebullient.

“That would be great. Most definitely our executive producer would love to talk about the possibility.”

Morton did not consult any Greeks, “not from a cultural perspective.”

“We did some work with classicists – and looked at translations of the Iliad over the last couple of centuries, to examine the different framing of that relationship throughout those different time periods.”

Would Morton construct a work of First Nations’ myth without consultation of First Nations’ people, Morton said, “absolutely not, there’d be a high level of consultation.”

“That’s an interesting provocation thank you for sharing it with me.”

As far as our myths, literature, philosophy, politics, and science, we Greeks gifted them to the world and the world can do what it wants with those gifts.

Holding Achilles is on in QPAC until September 10

For information on ticketing go to www.qpac.com.au/event/bf_dps_holding_achilles_22/

Video of the making: www.facebook.com/watch/?v=751055389280574&ref=sharing