What a day it is. A cloudless spring afternoon at Mackenzies Point, a flat shelf of rock poking out over the Pacific Ocean on the jagged southern headland between Sydney’s Bondi and Tamarama beaches. Tourists flock to this lookout, snapping selfies against a perfect, uninterrupted stretch of horizon where vivid blue sky meets deep blue ocean. On a perfect day just like this one in 1982, Elton John came to shoot a video for his hit song Blue Eyes, his white grand piano standing in the middle of this clifftop perch, encircled by a low stone wall.

Less than eight years later, this same spot would be the site of a horrific murder, the bare rock flecked with blood stains leading to the edge of the precipice. Scattered nearby were a pair of tinted prescription glasses, a light blue handkerchief smudged with red, a man’s wristwatch with a broken band, two keys on a ring and a page from a letter between mother and son – the belongings of a whippet-thin Thai man with floppy black hair called Kritchikorn Rattanajurathaporn.

On a frigid night in July, 1990, Kritchikorn, 31, stumbled here in a blood-soaked shirt, woozy from concussion after he and his companion, Geoffrey Sullivan, were subject to a savage Clockwork Orange-like attack by three young men wielding a claw hammer, a pipe and their fists. Sullivan was left lying in a pool of blood nearby; Kritchikorn, who had only arrived in Australia four months before, was chased along the cliff edge where he was either pushed or lost his footing, landing on a narrow ledge some metres below, before over a period of hours falling to another ledge. Here he would lie shivering, drifting in and out of consciousness, before turning and falling into the choppy waters below, where he would gasp for air for frantic seconds before drowning. Two days would pass before police divers discovered Kritchikorn’s body wedged between rocks below the surface.

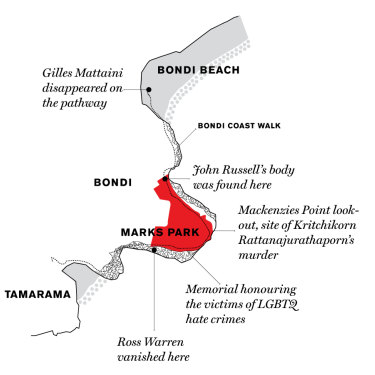

As our five-episode podcast Bondi Badlands, which launches today, explains, Kritchikorn was one of three men murdered on this headland in 1989 and 1990; it was also the scene of a number of assaults, a rape, a miraculous escape and a much earlier mysterious disappearance. The unvarnished fact is that late at night, Marks Park, a grassy verge capping the headland and the concrete pathway skirting the cliff face, had been a gay beat – a place where homosexual men would socialise and hook up – since at least the late 1920s. Gangs like the Bondi Boys (otherwise known by their graffiti tag PTK, or People that Kill) would prowl here, carrying out brazen acts of violence; it’s likely that at least a few were serial offenders; perpetrators of an anti-gay murder spree that swept across Sydney at the time.

This is no simple whodunnit; it involves a tangled tale of hate crimes involving multiple suspects, gangs comprising up to 30 members, some of whom circulated among other gangs across Sydney, composing a dark mosaic of murder. Teenage boys represented the bulk of these killers, but there were young women, too.

As our podcast shows, these types of homicide cases are among the toughest to solve. Kritchikorn’s slaying was one of the few at the time to receive a thorough police investigation. We will never know if he was still alive as he lay on that ledge, unconscious and out of view, after police arrived. In this case, at least, he was awarded a competent murder investigation by Detective Sergeant Steve McCann of Waverley police, resulting in his three killers being brought to justice and serving time in prison. This is a lot more than can be said for the other men killed here, or for that matter, the vast majority of other murders of gay men blighting Sydney at the time.

Almost a year to the day earlier, on another freezing night in July 1989, Ross Warren, a handsome, charismatic weatherman and newsreader from WIN-TV in Wollongong, vanished on this headland in the early hours of a Saturday morning. The 25-year-old left a few clues behind – his chocolate-brown Nissan, parked on a nearby street, his wallet tucked away in the glove box, and a thick clump of his keys, attached to a brass ring, discovered by two of his friends in a honeycombed rock face a couple of days later.

Warren’s mysterious disappearance drew a frenzy of media attention, but even this wasn’t enough to drive a proper investigation by Bondi police. Within three weeks of Warren’s disappearance, which is the focus of the first episode of our podcast Bondi Badlands, the senior detective coordinating the so-called “investigation” closed the case without a body being found, although he speculated it might wash up on a shoreline.

Earlier, on this long afternoon spent with the dead, I stopped at another point on the concrete pathway skirting the cliff face, past the Bondi Icebergs pool, surveying the rock platform 10 or more metres below. I fixed on the spot where a 31-year-old barman called John Russell landed after being dragged along the pathway and likely hurled over the cliff in the pre-dawn darkness of a hot November morning, only four months after Warren disappeared.

I pictured Russell in the moonlight, surrounded by his attackers, knowing there was no way out, but fighting for grim life anyway. He had his best years ahead of him that night, having just inherited $100,000 from his maternal grandfather, who’d run Clacks Cakes, a decades-old Bondi institution. Russell had been saying his farewells to Bondi: within days, he was to move to his dad’s property in Wollombi, in the Hunter Valley. He’d planned to build a kit home there and spend a year travelling around Australia.

Credit:

Back in the 1980s, Bondi was still known as a working-class area, albeit a rapidly gentrifying one: many locals paid rents in decaying art deco apartments with names like the Cairo Mansions or the Venice Flats, and street crime along the foreshore wasn’t unusual. This is where John Russell grew up; he’d long learnt to keep his wits about him. He was a man who exuded decency, warmth and strength, but he could also be handy with his fists – in the bars along Oxford Street where he worked during much of his 20s, he was the first barman called on to remove drunk troublemakers. And on the night of his death, Russell put up a real fight: inflicting damage on one of his killers, evidenced by a bunch of blond hairs still clutched in his left hand when his body was found at the cliff base – hairs containing the DNA of his murderer.

Less than a year earlier, in December 1988, the body of a brilliant, 27-year-old mathematician from the US, Scott Johnson, was found at the base of cliffs at Manly’s North Head. Like John Russell’s, Johnson’s death was dismissed by police as “not suspicious”, as a likely suicide. Scott’s brother Steve Johnson, a highly successful IT entrepreneur, hired investigative journalist Dan Glick in 2007 to look into the murder. What he unveiled was a shocking testament to continuing police inaction over three decades.

Last year, Steve offered to match the existing million-dollar police reward for information leading to the conviction of those responsible for Scott’s murder. Within a couple of months, a man from Sydney’s Lane Cove, Scott White, was arrested for the murder. A pre-trial hearing is due to begin in January next year. White, who is now 50, has pleaded not guilty.

“Cliffs were the easiest weapon; you didn’t have to carry anything with you. All you had to do was go to a certain location and hurt someone or push them off the edge.”

In what was perhaps another watershed moment this year, a 75-year-old man was arrested for the murder of Raymond Keam, a martial arts expert and father of two who was found beaten to death in January 1987 at Alison Park, Randwick, then a well-known gay beat in Sydney’s east. Stanley Early, also known as “Spider”, has been extradited to NSW after he was arrested in south-east Melbourne in August; this followed a million-dollar reward offered some months earlier. (Rewards of $100,000 have also been offered for information leading to the killers of Ross Warren and John Russell, as well as a French man, Gilles Mattaini, who disappeared from the Bondi coastal stretch in 1985.)

It’s quite possible that there were other clifftop murders in and around Bondi, and across other locations on Sydney’s northern beaches, in the years preceding the major thrill-kill years of the late 1980s. As Sue Thompson, a former state ombudsman’s investigator who joined the police force in 1990 to coordinate its liaison with the gay and lesbian community, tells me in the podcast: “Cliffs were the easiest weapon; you didn’t have to carry anything with you. All you had to do was go to a certain location and hurt someone or push them off the edge.”

“Things did not change magically in 1984 [when homosexuality was decriminalised in NSW]. In fact with the advent of AIDS, hate violence increased.”

For Thompson, becoming a liaison officer was deeply personal: one of her close friends had been murdered in a gay-hate killing only months before she took the role. The gay community’s mistrust of police at the time wasn’t helping to quell the violence. “Things did not change magically in 1984 [when homosexuality was decriminalised in NSW],” Thompson outlined in one of her reports. “In fact with the advent of AIDS, hate violence increased. It was my job to bring peace between police and the gay and lesbian communities and effect organisational change in police culture.”

If there remains any doubt that gay men’s lives were seen as of less value at that time, look at how these murders were investigated by the Bondi police. Ross Warren? A four-page police statement on his disappearance was not even forwarded to the Missing Persons Unit. There were no comprehensive door-knocks, no record of police divers searching the headland after his disappearance, not even an appointed investigator, despite friends and colleagues insisting this was not a suicide.

John Russell? His clothes were washed without any forensic analysis. The only person who gave evidence at the first inquest into his death in July 1990, which lasted all of 35 minutes, was a sergeant from Bondi police, who dismissed it as “death by misadventure”. Russell’s younger brother Peter strode out of the courtroom in disbelief and disgust.

The Warren and Russell cases lay dormant. Then, on a brisk autumn day in 2000, a detective at Sydney’s Paddington Police Station, Steve Page, was moved by a series of letters from Ross Warren’s mother, Kay, who had one simple request: for her son to be officially declared dead, so she could tend to his affairs. As Sydney partied to the Olympics, Page created a new investigation – code-named Taradale – and began joining the dots between the two murders.

Detective Steve Page led an investigation into the murders at Bondi, Operation Taradale, that would consume years of his life. He has since left the force. Credit:James Brickwood

After 18 months of solid investigation, Page needed more witnesses to come forward – and more public attention on the cases. He struck on the idea of staging a re-enactment of John Russell’s fall from the Bondi clifftops using a weighted, flexible dummy, and chose a quiet news day, a Sunday morning. As a result of the media attention, a handful of people came forward to tell their stories, among them a man who had been dragged to the cliff edge only a month after Russell’s death. “Let’s throw him off where we threw the other one off,” one of his assailants had yelled, near the same spot Russell had met his fate. But the man, 22 at the time, had made a miraculous escape – and lived to tell his story. Sadly, it was after this that another strange disappearance on the headland came to light, that of 27-year-old Gilles Mattaini.

“Let’s throw him off where we threw the other one off,” one of his assailants yelled.

Operation Taradale rattled more than a few cages, and resulted in a coronial inquest in 2005. In her findings, deputy state coroner Jacqueline Milledge delivered a scathing assessment of the early police investigations into the murders of Russell and Warren, describing them as “lacklustre”, “disgraceful” and “shameful” to a packed courtroom while applauding Page’s work in unveiling a dark web of hate.

A dummy was thrown over the cliff at Bondi as a re-enactment of John Russell’s murder. The re-enactment made the evening news and resulted in new witnesses to the violence coming forward to police.

In the late 1980s and early ’90s, Sydney’s gay and lesbian community was under siege (bashings and murders of gay men were also happening in Melbourne, Brisbane and Adelaide, but not on the same scale). Something, however, broke after the murder of Kritchikorn Rattanajurathaporn.

The escalating violence brought a sea of angry protestors that filled Macquarie Street in front of state parliament. Activists splattered red paint over 11 city buildings, including state parliament, the Downing Centre court complex, and the headquarters of Channel 10 and The Sydney Morning Herald, then located in Jones Street, Ultimo.

Self-defence classes were springing up in inner-city gyms and community groups, and a group of gay volunteers – some of them former members of the army, navy and police force – began foot patrols along Oxford Street and Darlinghurst Road.

Oxford Street foot patrol in 1991.Credit:Reuters

Still, the murders continued. Across town, staff at Cleveland Street High School in Redfern were working in fear after an office worker, Richard Johnson, was killed in Alexandria Park in January 1990 by a group of teenage boys that included students from their school. In May, one of their own, social science teacher Wayne Tonks, was murdered in his Artarmon apartment by two young men (not his students).

There was outrage when the so-called gay panic defence, a cruel wrinkle in the law that enabled killers to claim an alleged sexual advance provoked them into a murderous rage, was used in the murder trial of Christopher McKinnon, arrested for killing Maurice McCarty, a technician with the Australian Ballet, in April 1991. As McCarty lay dying, his killer stole his car keys, ransacked his Victorian semi in Newtown of jewellery and other valuables, and sped off in his victim’s Nissan sedan. Although McKinnon was convicted of murder, he was later acquitted on appeal.

The Bondi Badlands podcast is about the slow road to justice for the victims’ distraught families, beginning with their angry disbelief at the initial investigations, when police not only failed to link a series of awfully similar murders, but lost or destroyed vital forensic evidence. “Many police at the time would have thought of us as sick, perverted or criminals, given our communities’ place in history, and how we had been ‘classified’ and legally framed in the past,” notes Nic Parkhill, CEO of the LGBTQ health organisation, ACON. “Some police officers may have been indifferent, others thinking we got what we deserved, and for some, there would have been a total lack of understanding of the context in which these crimes took place. I think many of these attitudes led to a willingness to write some of these crimes off as suicide, despite family protestations.”

“Some police officers may have been indifferent, others thinking we got what we deserved, and for some, there would have been a total lack of understanding of the context in which these crimes took place.”

Parkhill concedes that the culture of the NSW police force reflected broader societal norms of the time, although possibly exacerbated by a mostly male staff and the AIDS crisis, which provided those with an agenda against gay men with the perfect ammunition to stigmatise the LGBTQ community even more. Earlier this year, the findings from an 18-month parliamentary inquiry, Gay and Transgender Hate Crimes between 1970 and 2010, found that the NSW Police Force had failed in its responsibility to properly investigate historical hate crimes. The report concluded that acknowledging past wrongs is a vital step towards delivering justice for the loved ones of victims and survivors.

Loading

But only a follow-up judicial inquiry, argue many observers, would carry real teeth.

“A judicial inquiry would have investigative powers, and importantly, the ability to compel people to give evidence,” observes Parkhill. “People who may otherwise be happy to remain in the shadows for fear of recrimination or association would be required to speak and give evidence … people like former police officers, health service staff such as nurses and doctors, neighbours in key localities where crimes occurred, members of the then judiciary, and many others. That is powerful.”

I’ve followed these murders since 2005, when I was covering Coroner Jacqueline Milledge’s inquest inside the mustard-coloured bunker of the Glebe Coroner’s Court. My book on the murders, Bondi Badlands, was published back in 2007, and over the years one question has continued to haunt me: what turns young men into murderers of gay men? The pop-psych explanation we so frequently hear – that those who commit violent offences against gay men must have suffered sexual or physical abuse themselves – doesn’t necessarily hold up to close scrutiny. Some of the perpetrators came from loving homes and stable families.

“A judicial inquiry would have investigative powers, and importantly, the ability to compel people to give evidence. People who may otherwise be happy to remain in the shadows for fear of recrimination or association would be required to speak and give evidence.”

Throughout Steve Page’s investigation, the path kept winding back to three or four main suspects. We now know, through the Scott Johnson case and the recent arrest in relation to Raymond Keam’s murder, that a continued media focus will keep these murders in the public eye, and slowly but surely tighten the net around the perpetrators.

A memorial to honour the victims of LGBTQ hate crimes is now being built on the headland at Bondi. The memorial, called Rise, designed by Urban Art Project, is expected to be open to the public this month.Credit:Courtesy of Waverley Council

My walk around the headland finishes up in a corner of Marks Park with jaw-dropping views out to sea and across to Tamarama. Here, a memorial is being built to honour the victims and survivors of LGBTQ hate crimes. A six-level stone terrace, the memorial will be open to the public later this month, and contains fitting tributes to those who lost their lives here. Make no mistake about this: these men, like so many others at the time, were slaughtered because they were gay. But it wasn’t just sexual identity that unified them: they were all denied a full, joyful life. As Jacqueline Milledge reflects powerfully on our podcast, we owe it to the victims, for they were loved and decent men.

To read more from Good Weekend magazine, visit our page at The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age and Brisbane Times.

The best of Good Weekend delivered to your inbox every Saturday morning. Sign up here.