It was a 13-page brief with a simple title: “We Demand.” In a cover letter, contributors Brian Waite and Cheri DiNovo outlined the goal of the document and its accompanying protest:

“On Saturday afternoon, August 28, 1971, homosexual men and women and their supporters will rally in front of Parliament Hill in support of this brief. This action will be the first such public demonstration of its kind in Canada. Moreover, it will be the opening of a continuing public campaign until the just and reasonable reforms in the enclosed brief are achieved, and until the day when homosexual men and women are as free and equal as our heterosexual brothers and sisters.”

The date of Canada’s first major gay-rights protest was chosen to mark the second anniversary of the implementation of Bill C-150, which made amendments to the Criminal Code that decriminalized consensual homosexual acts between adults aged 21 and older. While old prejudices died hard, there were promising signs: a 1970 survey of London residents regarding criminal punishment found that more than half agreed with the new legislation when it came to homosexuality.

Our journalism depends on you.

You can count on TVO to cover the stories others don’t—to fill the gaps in the ever-changing media landscape. But we can’t do this without you.

But discrimination and misconceptions were still the norm. During the summer of 1971, the

federal government provided a $9,000 Opportunities for Youth grant (worth approximately $54,000 today) to the Community Homophile Association of Toronto to educate the public about homosexuality. One of the key services it offered over a 13-week period was a telephone hotline, which the group hoped would help dispel public stereotypes of homosexuals as crossdressers, pedophiles, and sex obsessives. “We are no more hung up than the heterosexual community,” program worker Patricia Murphy told the Toronto Star.

That summer also saw the assembling of “We Demand.” Drafted by Toronto Gay Action (to which DiNovo and Waite belonged), the document listed a dozen organizations from across Canada as supporters, including groups based in Guelph, London, Toronto, and Waterloo. Intended to reflect a broad political appeal that would be acceptable to moderates within the community, its focus was on legal and regulatory reforms addressing discriminatory measures still on the books, rather than on the sexual liberation some desired.

The document presented 10 demands to the federal government:

- Remove the terms “gross indecency” and “indecent acts” from the Criminal Code and replace them with specific offences that applied universally, regardless of one’s sexuality

- Remove those same terms as grounds for being indicted as a “dangerous sexual offender”

- Legislate a uniform age of consent for heterosexual and homosexual sex

- Amend the Immigration Act to remove barriers for homosexuals

- Ensure equality of employment at all government levels

- Amend the Divorce Act, which placed homosexual acts in the same category as mental and physical cruelty and rape as grounds for divorce

- Award child custody based on parental merit, not sexuality

- Reveal whether it was true that the RCMP had spied on homosexuals in order to fire them from federal jobs

- Enact the right for homosexuals to serve in the armed forces

- Amend human-rights legislation to provide the same freedoms for homosexuals as for everyone else

The document concluded with a call for federal officials to, in good faith, immediately begin discussions with homosexual organizations and provide a public response to the demands. A letter from the August 28 Gay Day Committee inviting Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau to the protest said that, while the amendments had been a good first step in achieving full legal equality, “much of the continued widespread hostility and discrimination against homosexuals in the private sector is directly supported by certain government policies and laws.”

Trudeau didn’t show up to formally accept the brief; in an August 24 letter, his appointments secretary wrote, “In view of his many other commitments, I fear it just would not be possible for the Prime Minister to meet with you on August 28th.”

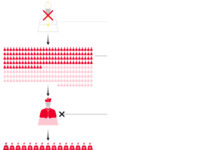

Between 100 and 200 people participated in the protest, which occurred on a rainy Saturday afternoon at the Centre Block. Attendance posed various risks: if protesters were recognized, they could face potential professional and personal repercussions. Several invited guests declined to attend from fear of being outed or associated with gay-liberation groups.

The protestors chanted slogans like “two, four, six, eight, gay is just as good as straight” and carried banners with such slogans as “Support Your Local Monarch — Hire a Queen.” Some signs functioned better than others; several written in magic marker on white cardboard dissolved in the rain into what participant Jearld Moldenhauer described as “unreadable gobs of paper.”

The main speech was delivered by Charlie Hill, president of the University of Toronto Homophile Association. He noted that changes to the Criminal Code had done little to help. “Even today, homosexuals are losing their jobs, being kicked out of their churches, having their children taken away from them, and being assaulted in the streets of our own cities,” Hill noted. “What have we done to deserve this? Love. All we want to do is love persons of the same sex and live our lives as we decide for ourselves.”

“Today marks a turning point in our history,” Hill declared. “No longer are we going to petition others to give us our rights. We’re here to demand them as equal citizens on our own terms.

He ended with the declaration, “Gay is proud, and gay is good. Let’s say it wherever we go.”

While there had been fears about the potential of violent reaction from spectators, only a few curious onlookers, Parliament Hill police, and reporters watched that day. After the speeches were over, protestors went off to find dry clothes and warm beverages. On the same day, up to 20 people conducted a similar protest in Vancouver in front of that city’s courthouse. Across the Atlantic Ocean, more than 300 people protested in London’s Trafalgar Square against the United Kingdom’s Sexual Offences Act.

Just over two weeks after the demonstration, Gays of Ottawa was founded. Within two years, it had helped establish a Gay Pride Day in the nation’s capitol, an achievement in a city where the LGBTQ community had long dealt with discrimination and persecution in the public service.

Over the course of the 1970s, there were a trickle of changes. Toronto banned discriminatory municipal hiring practices based on sexuality in 1973; Ottawa and Windsor followed suit three years later. A revised Immigration Act, passed in 1976, ended the ban on homosexual immigrants. But the tackling of the issues raised by “We Demand” didn’t gain greater momentum until the growth in LGBTQ activism following the bathhouse raids in Toronto in 1981.

Several months after the demonstration, the first issue of The Body Politic — a journal focusing on “gay liberation” — was published in Toronto. It contained the text of “We Demand” along with several articles on where to go from there. A piece titled “A Program for Gay Liberation” expressed some optimism about the future. “Eventually,” the author wrote, “we will win the support of the vast majority of straights because they are too oppressed by the distortion of human sexuality, relationships and love which is called ‘normal’ in this society. They will realize they have no stake whatsoever in hating or fearing homosexuals or homosexual feelings of their own.”

Sources: “1971 We Demand March” exhibit, the Arquives; “We Demand” entry on The Canadian Encyclopedia; the November-December 1971 and September 1981 editions of The Body Politic; the Winter 2014 edition of The Journal of Canadian Studies; the August 28, 2006, edition of the Ottawa Citizen; the August 10, 1971, edition of the Toronto Star; and the August 30, 1971, edition of the Windsor Star.