When The Woodward, Detroit’s oldest-running gay bar, burned in a massive fire last week, it spurred a conversation about the history of the bar itself, but also where it was situated in Detroit gay history more broadly — and how to remember and celebrate its significance in the gay community while looking toward the future.

The fire happened in the middle of Pride Month, and not just any Pride Month in Detroit: This year marks 50 years since the city’s first Pride march, held June 24, 1972 to demand “full civil rights for gay people” and a repeal of all anti-gay laws, the Free Press reported back then.

The march, officially called Christopher Street ’72, was itself a remembrance of the uprising at the Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street in New York City on June 28, 1969, when protests broke out in response to a police raid at a gay bar.

In its 70-odd years, The Woodward has been part of many intersecting stories of gay life and culture in Detroit, including policing of gay spaces, ownership shifts, racial segregation and population trends in the city.

Curtis Lipscomb, executive director of nonprofit LGBT Detroit, calls places like The Woodward “safe, brave spaces.” Why?

“You have to be daring in the middle of America to own any kind of property that welcomes peculiar people,” Lipscomb said.

In 1954, William Karagas bought a bar on Woodward Avenue north of Baltimore Street, blocks away from the Fisher Building and the old General Motors headquarters on West Grand Boulevard. (The original location was a few doors down — it moved to its current spot a few years later.)

The Woodward, operated by William and his brothers Andy and Sam, served the GM lunch crowd by day, but attracted a different patronage by night, when it turned into a cocktail lounge and cruising bar.

The owners said they never set out to open up a gay bar.

“We just opened it up and whichever way it went, it went,” Andy Karagas told “Gayzette” in 1973 (as reported in Andy’s obituary in 1997). “And when it went gay all the way, we kicked out all the straights that night.”

Andy served as the “host” for evenings at The Woodward. He later came out as gay.

At the time, owners of gay bars in Detroit were mostly not gay themselves. Gay sex was a crime in Michigan — as it had been since the 1800s — and police frequently harassed and arrested gay people and raided gay bars.

“It was technically illegal to operate a bar that was a rendezvous for homosexuals,” said Tim Retzloff, adjunct assistant professor of history and LGBTQ studies at Michigan State University. “If you were a straight bar owner, you had to be careful — you wanted to protect your clientele, but you also didn’t want to get on the wrong side of the police.”

Bars at the time, gay and otherwise, sometimes paid off police to be left alone. Many bar owners were also known to bail out customers who were arrested in raids and sting operations

The Woodward provided a safe haven for white gay men. But not everyone felt at home there. Like many gay bars of its era, it did not embrace people of color.

“My first engagement unfortunately wasn’t one that was welcoming,” Lipscomb said. “Like many bars of a certain time, it wasn’t welcoming to nonwhites. The Woodward had that reputation wholeheartedly when I first started attending.”

In that way, The Woodward was not unlike most other early gay bars in Detroit.

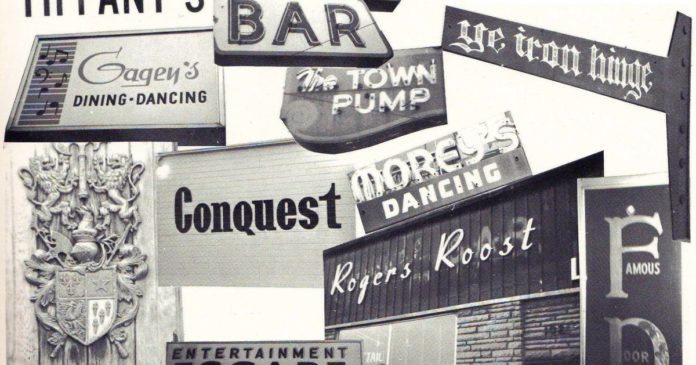

Starting after World War II and into the 1960s, several gay bars were clustered around Farmer and Bates streets in downtown Detroit, including Club 1011, La Rosa’s and The Silver Dollar. Very few gay bars at the time catered to Black patrons, although there were two in Paradise Valley that Retzloff has identified in his research: The 705 and the Rain-bo Music Club.

Lesbian bars were also few and far between. There was The Palais, on Beaubien in Greektown, which opened in 1949, and the Sweetheart Bar at Third and Selden in the Cass Corridor, which both attracted working-class crowds and had reputations as rough places with frequent fights. Fred’s Bar, which opened in 1952, welcomed a more subdued middle-class clientele, according to an essay by Roey Thorpe, “The Changing Face of Lesbian Bars in Detroit, 1938-1965.”

Spaces for Black queer women were so hard to find that Ruth Ellis and her partner Babe Franklin — who also happened to run Michigan’s first woman-owned printing shop — opened their home on Oakland Avenue for gatherings and parties. Their place was known as “The Gay Spot.”

More gay hangouts began to crop up beyond downtown in the ’50s and ’60s. In 1959, Sam “Bookie” Stewart, who had managed The Silver Dollar for his brother-in-law, opened The Diplomat at Second and Pingree in New Center in 1959. In 1970, he purchased an old supper club called Frank Gagen’s on West McNichols just south of Palmer Park, which became Bookie’s Club 870.

Gay ownership of gay bars became more common in this era. Menjo’s, which still exists, was gay-owned when Mike Crawford, Henry Trent and Joe LaRosa, Jr. opened it next door to Bookie’s in 1974. Diane Bono, Donna Chartier and June Reynolds opened the first lesbian-owned lesbian bar, The Casbah Lounge, in 1974 on Plymouth Road.

Gigi’s, on West Warren near the Southfield Freeway, will take on the mantle of the oldest operating gay bar in Detroit if The Woodward does not survive. It dates its founding to 1973, when the former supper club was purchased by Tony Garneau — a gay man and one of the founders of Bars and Towels, Inc., an early association for owners of gay bars and businesses.

Other notable Detroit gay bars of the 1970s include The Famous Door, on Griswold near Grand River in Capitol Park, which had been a straight bar until it was purchased in 1972 by Ernest Backos, the owner of the old Club 1011, which by then had been sold and demolished for parking. The Famous Door became a Black gay nightclub “famous” for its music and dancing. On the east side, at Seven Mile and Van Dyke, an interracial gay couple, Bobby Calvert, who was Black, and Dan Campbell, who was white, opened Todd’s Sway Lounge in 1975. Todd’s was one of the few racially integrated Detroit gay bars in its day.

By the mid-1980s, there were about four dozen gay bars in Detroit, compared to about a dozen 20 years earlier.

Retzloff said several factors played into the rapid growth of the gay bar scene in Detroit in the ’70s and ’80s, even as Detroit’s population declined. Though many gay people had moved to the suburbs, few gay bars existed outside Detroit until the mid-1990s, due to trenchant suburban anti-gay discrimination. The relatively new interstate highway system also made it easier to get around the metro area somewhat discreetly. And as factories closed throughout those decades — particularly Dodge Main in 1980 — bars that had previously served workers shifted to serving a gay clientele.

“The ugly part of that is that the owners preferred to have gay customers to having African American customers,” Retzloff said.

Systemic and economic racism also made it difficult for Black business owners to get a foothold in the scene.

“Because of the capital investment that it takes to run a bar and the cost of a liquor license, there were always far fewer Black (owned) gay bars,” Retzloff said.

Detroit’s gay bar scene declined in the ’80s and ’90s as Baby Boomers aged out of their bar-going years and the HIV/AIDS epidemic renewed discrimination against gay people and decimated the community.

Today, there are about 10 gay bars in the metro Detroit area, according to a listing in OutPost magazine — not including the Woodward.

Few of its landmarks remain. The site of The Famous Door is a parking lot now. The Bookie’s Club 870 building burned down in 1988. The Gold Dollar, perhaps better known as a hotspot of Detroit’s garage rock revival in the 1990s, was a drag bar in the 1950s; it was demolished after a fire in 2019. Even the home of Ruth Ellis, one of Michigan’s most widely known gay activists, is a vacant lot today.

These are just a handful of examples of gay bars, clubs and gathering spaces that have been razed over the years. But historians and activists have tried to save what they can — and keep the stories alive.

LGBT Detroit has a collection of archives and artifacts from Detroit’s notable LGBTQ sites, including The Famous Door, to which it paid homage at a fundraiser in 2018. It is also home to the sound system of Club Heaven, a gay dance club that opened at Seven Mile and Woodward in 1985. Preservation of the Club Heaven sound system is a partnership project with the Detroit Sound Conservancy, which will host a celebration of Club Heaven on July 7.

Now, LGBT Detroit has begun to grapple with how to help the community process and move forward from the loss of The Woodward. Despite its early history as a white bar, changes in management and in the community over the years had made The Woodward one of the most prominent Black LGBTQ spaces in town.

“Yes, it’s a nightclub, yes, it’s for social convening, but it is the longest-running Black (LGBTQ) bar in the city of Detroit,” said Tieanna Burton, project manager and designer at LGBT Detroit. “And while it was not owned by Black people, Black people were predominantly the patrons of that business, who came in for fellowship there, who performed there, who were the DJs there, who were security there. It employed Black people, and it also provided Black folks a space to be authentically themselves.”

Last week, the nonprofit organized a community conversation about The Woodward to give people a chance to share their memories and talk about what the future of Black LGBTQ spaces in Detroit might look like.

“It is extremely important to recognize and to celebrate these spaces that queer people have built over the decades,” Lipscomb said. “They have invested their time, their savings and their sweat for people like us to be free. We honor that. As The Woodward is remembered and people talk about their memories with The Woodward, it is important to look forward. What does the movement look like as they seek new nightlife experiences?”