THEO PANAYIDES meets a gay Palestinian man who has just written his life story. He finds someone who has lived a charmed but traumatic life, who had dealt with feeling displaced and out of place

“I’ve had a charmed life. A beautiful, loving family. A great education. Friends all over the world and money to travel and see them. The trauma, however, has also been great.”

That’s 56-year-old Madian Al Jazerah from his just-published memoir Are You This? Or Are You This? (written with Ellen Georgiou), the story of his life as a gay Palestinian man. The list of acknowledgments at the end of the book is quite long but “the biggest thanks,” he says, “go to Mama – Marwa Nayef Hindawi – who has kept us all so tightly knit through lessons of love and strength”. Yet it was also his mama who gave the book its title, by her reaction when he finally came out as gay. “Are you this?” she asked, making a hole with her hand – “or are you this?”, poking at the hole with the index finger of her other hand. If he was the poker, that was okay, he was still a man: “You can get married. You can marry a lesbian.” Being the poked, however, was beyond the pale.

That’s 56-year-old Madian Al Jazerah from his just-published memoir Are You This? Or Are You This? (written with Ellen Georgiou), the story of his life as a gay Palestinian man. The list of acknowledgments at the end of the book is quite long but “the biggest thanks,” he says, “go to Mama – Marwa Nayef Hindawi – who has kept us all so tightly knit through lessons of love and strength”. Yet it was also his mama who gave the book its title, by her reaction when he finally came out as gay. “Are you this?” she asked, making a hole with her hand – “or are you this?”, poking at the hole with the index finger of her other hand. If he was the poker, that was okay, he was still a man: “You can get married. You can marry a lesbian.” Being the poked, however, was beyond the pale.

Madian’s mother is an educated woman, a former teacher and writer; his father worked for an oil company, the family had money in general (at least in Kuwait, before being expelled in 1990; more on this later). It wouldn’t be right to dismiss her as an ignorant bigot – and indeed the clan are still very close, mother and four out of five siblings (including Madian) living in the same block of flats in Amman. ‘Are you this, or are you this?’ is absurd, of course, irrational on the face of it: even if one presumes that homosexuality is ‘wrong’, the poker – the man who gets aroused by another man – is obviously much more culpable than the other, the passive recipient. Yet his mum’s reaction didn’t stem from ignorance per se, it stemmed from a cynical truism widely accepted in the Middle East, and by Palestinians in particular: the world – including, inevitably, sex – is based on power.

“It’s about power, it’s about value,” agrees Madian, sitting on his balcony in the MAP Boutique Hotel in Nicosia, a few hours before a book launch at the Centre for Visual Arts and Research. “I’m not talking very much in the book about homosexuality, but I’m talking about power and patriarchy, and how this is used against women and against men, and against the gay community as well.” In prisons, he notes, new arrivals are routinely sodomised as a show of power, to establish their place in the pecking (or poking) order. In heterosexual sex, the penis is a power tool, men often viewing the act as an act of domination. In his book he recalls an incident from childhood, when a neighbourhood teen was applauded by his peers for having allegedly had sex with a donkey: “He was a man, so much so that he had even fucked a donkey”. Talking to me, he recalls guys “being raunchy”, wrestling for fun – and the victor’s humorous threat, after he’d pinned his opponent to the ground, to penetrate him sexually as a final act of humiliation.

This was all quite upsetting to the young Madian – because his own fantasies were set from an early age, and inevitably involved other males. “When I was a child I wasn’t thinking sex, of course; I was thinking ‘Who’s my hero? Who do I want to be saved by?’. If I created adventure stories, Superman or whatever, I was being saved by Superman”. Growing up, he learned to equate what he increasingly knew himself to be with feelings of guilt and shame. The word ‘gay’ didn’t even exist in Arabic, there were only derogatory terms; it was only years later, in the late 00s, that a “vocabulary” was created – actually by a group of LGBT activists including Madian himself, who’d attend large human-rights conferences (the kind with simultaneous translation) and shame the poor Arabic translator into using the correct words to describe them.

“I was always desperate to fall in love with a woman,” he recalls ruefully. “I wanted my parents’ life. Their template, the heterosexual template of love and children and marriage – and the party, and the wedding – that whole template is a beautiful template, and I always wanted that. But I couldn’t do it. I just couldn’t do it… I desperately tried to be with women, I desperately tried to fall in love with them – and I did, but it wasn’t the kind of falling in love that had sex attached to it.” For years he pretended to be straight, and would even complain to friends about people assuming he was gay just because he was flamboyant and effeminate; it wasn’t till his late 20s – in San Francisco, the most gay-friendly city in the world – that he came out ‘to himself’, as he puts it, then soon after to his siblings (though only because he thought he had terminal cancer; that’s a story in itself, described in the book) and only then, years later, to his parents.

There were other, auxiliary traumas – though this isn’t just about the traumas. Madian was molested as a child (by a male relative, at the age of six), denigrated for being gay at various points in his life – and even San Francisco ended badly, when he and a friend (a Cypriot, as it happens) were gay-bashed on the street by a couple of thugs. The man sitting opposite me at the MAP Hotel has been through a lot in life – though you wouldn’t really know it from his energy. Ellen Georgiou, the old friend and professional writer who structured his life into book form (and is sitting in on our interview) describes him as “very playful”, and he gives that impression: bald, blue-eyed, soft-spoken, physically slight, with a trim goatee, a wry sense of humour and a hint of a dainty, mincing manner that must’ve been more prominent in his youth. “I’m a people person,” he replies when I ask what his biggest strength is. “You have a problem with somebody? – send me! I’ll settle it, I’ll talk with them… I know how to bring people together.”

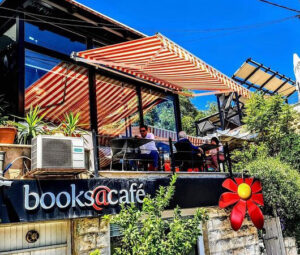

As a student (at Oklahoma State, where he trained as an architect) he was fun, bohemian, endlessly sociable; “I was playful and happy – that was my nature,” he reports in the book, though some disagreed (“Why do you walk like a fag?” they’d call out). More recently, in Amman, he’s parlayed that love of people into [email protected], the first internet café in the Arab world (it opened in 1997) but also a beacon for other “displaced” types including refugees and the LGBT community. Ellen intervenes, feeling the need to add something that she knows Madian will be too modest to say for himself. Are You This? Or Are You This? is published by Hurst Publishers in London, she explains – and not only did they agree to take the book almost immediately, but one of the editors also reached out to them with the following comment: “My partner lived in Amman for a year, and he said Madian Al Jazerah is a legend”.

Now we’re getting somewhere – and indeed this is where the story blossoms, building to a satisfying third act. The second act was perhaps the most depressing, starting in 1990 when Yasser Arafat expressed support for Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait – and, in retaliation, all Palestinians were summarily expelled from the country once the war was over, making Madian a refugee and his parents refugees twice over.

He, still in the US at the time, was devastated; “I’m already carrying the Palestinian chip – but then the country you thought you were safe in, Kuwait, kicks you out”. His family relocated to Amman, forced to flee with just the proverbial shirts on their backs. He recalls his mum putting on “all her gold bracelets and diamonds” and driving through Iraq to Jordan in the sweltering heat, wearing lots of layers on top to conceal the valuables.

Fast-forward a couple of years, to that street fight in San Francisco – and Madian was beaten badly, getting his hand broken in five places in the melee, but in fact it could’ve been worse: their attackers, it turned out, had a gun, and murdered a man (presumably still hopped-up from the fight and whatever drugs they were on) just a few minutes later. Madian agreed to identify one of the killers – then, rather than enrol in a witness protection programme, decided to return to the Middle East, joining the others in Amman. His life was shifting into a new chapter – but he wasn’t in a good place, stricken with a kind of cumulative PTSD. His psyche had been “pounded so many times, by so many issues… And being robbed of all my rights, on all levels, created the refugee mentality – created the broken, devalued, vulnerable me. Who accepted the short end of the stick in everything I did.”

Was he very resigned to everything?

“I was like this,” he replies, pulling in his head as if to ward off a blow. “Head in my shoulders, and – you know, I’m not going to ruffle any feathers. When you show weakness, you get dominated,” adds Madian grimly. “It took me 10 years to discover what I was doing.”

There it is again: power, domination, forced to be the poked instead of the poker. Having to renounce his childhood home – and being powerless to do anything about it – was, in many ways, the last straw, added to the stress of being gay (and still in the shadows) and the constant ache of being Palestinian, a people who’ve spent the past 70 years being endlessly pushed around. Being Palestinian means being powerless (the national motto is instead ‘sumud’, an oft-used word meaning ‘to stand firm’ or ‘to persevere’), just as being a gay man is akin to being a refugee, both being “displaced” – out of place – in different ways. Madian isn’t really power-driven, his most pressing needs being love and acceptance; he’s playful, sociable, a fun-loving person, a people person. Yet he’s also amassed a certain power, in his way, over the past few years – and also become an activist, albeit a kind of accidental activist.

He helps people; that’s his most obvious gift. He’s just back from LA, having gone all that way to help a friend in trouble. [email protected] was perceived as a safe space, he tells me, so they started getting gay people seeking refuge, and battered wives who’d fled their husbands, and village girls looking for a new life – “and they all end up at my place, and I end up helping them out”. Some he’ll help financially, “some I take to hospitals, and I find them a safe place to hide, and then look for ways to smuggle them out of the country”. He and others have also formed a pan-Arab LGBT network, helping those who need it – and he’s also worked extensively in the Syrian refugee camps (housing over a million refugees) that have sprung up in Jordan, trying to “raise my voice” and alert the UN to harassment of those who are gay or trans. In short, he’s become a legend.

He helps people; that’s his most obvious gift. He’s just back from LA, having gone all that way to help a friend in trouble. [email protected] was perceived as a safe space, he tells me, so they started getting gay people seeking refuge, and battered wives who’d fled their husbands, and village girls looking for a new life – “and they all end up at my place, and I end up helping them out”. Some he’ll help financially, “some I take to hospitals, and I find them a safe place to hide, and then look for ways to smuggle them out of the country”. He and others have also formed a pan-Arab LGBT network, helping those who need it – and he’s also worked extensively in the Syrian refugee camps (housing over a million refugees) that have sprung up in Jordan, trying to “raise my voice” and alert the UN to harassment of those who are gay or trans. In short, he’s become a legend.

Power rules the world, that goes without saying – but “I’ll tell you where love kicks in: love holds you together”. His family’s love was an anchor in troubled waters – and his activist work also stems from love, a love of humanity. It’s significant that he focused so much on creating a vocabulary, a non-offensive way of referring to LGBT, optimistically certain that, once the words were there, people would be able to discuss and work things out. Madian thrives on people, studying them, watching them; he looks at their appearance, their body language, “and a million questions come in my head” – especially those whose posture is a bit like his own used to be, “who’ve got their heads in their shoulders… I wonder what life has done, where is he oppressed or hurt that makes his body language this way? This is the first thing I notice in people.”

He himself has grown as a person; it’s even more apparent now, with his life laid out in book form like an architect’s blueprint. He’s still (I suspect) quite easy-going and non-confrontational, still driven mostly by a wish to love and be loved – but he’s come into himself, and no longer needs the survivor’s coping mechanism of keeping his head down and accepting the short end of the stick. Bullies and homophobes no longer sniff out weakness, as they did for so long. “At 56, you are not going to step on my toes, and I’m not going to lie anymore,” declares Madian Al Jazerah. “I’m not going to hide, I’m not going to lie. Enough! Halas! Enough!” Is he this, or is he this? Now he knows: he’s exactly this.