Home Blog

Trailblazing gay rights activist honored for turning his firing from Army...

Trailblazing gay rights activist honored for turning his firing from Army into lifelong mission NBC News

When George Wendtâs Norm taught us gay stereotypes are the real...

When George Wendtâs Norm taught us gay stereotypes are the real joke in one of Cheersâ most seminal episodes Advocate.com

Is there a âgay voiceâ? Why this student’s controversial thesis went...

Is there a âgay voiceâ? Why this student's controversial thesis went so viral USA Today

Winners of the 2025 Sports Business Awards – Sports Business Journal

Winners of the 2025 Sports Business Awards Sports Business Journal

Conference expulsion? No penalty structure? Questions mount as college sports enforcement...

Conference expulsion? No penalty structure? Questions mount as college sports enforcement comes into focus CBS Sports

Debate swirls over Democrats, young men & whether gay comms directors...

Debate swirls over Democrats, young men & whether gay comms directors can talk sports Queerty

Gaza health system ‘stretched beyond breaking point’, WHO warns – BBC

Gaza health system 'stretched beyond breaking point', WHO warns BBC

âI read him my seven-page sex sceneâ: Gay Bar author Jeremy...

âI read him my seven-page sex sceneâ: Gay Bar author Jeremy Atherton Linâs transatlantic love story The Guardian

New memorial to gay victims of Nazi persecution unveiled in Paris...

New memorial to gay victims of Nazi persecution unveiled in Paris PinkNews

‘Disheartened, angry’: Auckland high school cancels LGBTQ+ event after threats –...

'Disheartened, angry': Auckland high school cancels LGBTQ+ event after threats NZ Herald

Watch Sports, Media & Ownership: Leaders Redefine the Game – Bloomberg

Watch Sports, Media & Ownership: Leaders Redefine the Game Bloomberg

Diseases are spreading. The CDC isn’t warning the public like it...

Diseases are spreading. The CDC isn’t warning the public like it was months ago NPR

Gay Employee Wins Suit Against CRS for Denial of Health Benefits...

Gay Employee Wins Suit Against CRS for Denial of Health Benefits for Husband New Ways Ministry

For LGBTQ+ Representation to Matter, Queer Media Censorship Must End. –...

For LGBTQ+ Representation to Matter, Queer Media Censorship Must End. trillmag.com

Adolescent health is at a tipping point, global analysis suggests –...

Adolescent health is at a tipping point, global analysis suggests Medical Xpress

Best possible NFL flag football team for 2028 Olympics: Commanders’ Jayden...

Best possible NFL flag football team for 2028 Olympics: Commanders' Jayden Daniels could lead Team USA stars CBS Sports

Gay Senate candidate Chris Pappas: The government shouldn’t limit trans people’s...

Gay Senate candidate Chris Pappas: The government shouldn't limit trans people's health care Advocate.com

Community demands transparency after sudden closure of Racine LGBT Center –...

Community demands transparency after sudden closure of Racine LGBT Center TMJ4 News

Colorado’s A Basin celebrates the spirit of the mountains and the...

Colorado's A Basin celebrates the spirit of the mountains and the LGBTQ+ community with Gay Basin event CBS News

Florida’s oldest gay bar reopens in West Palm Beach, 5 years...

Florida's oldest gay bar reopens in West Palm Beach, 5 years after it burned down WPTV

Phallic symbols, bare buttocks and warrior poses: how physique magazines grew...

Phallic symbols, bare buttocks and warrior poses: how physique magazines grew a cult gay following The Guardian

Energized by Kennedy, Texas ‘Mad Moms’ Are Chipping Away at Vaccine...

Energized by Kennedy, Texas ‘Mad Moms’ Are Chipping Away at Vaccine Mandates The New York Times

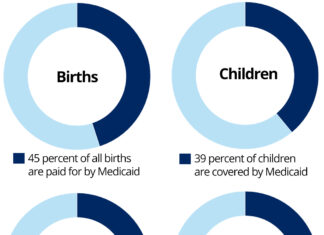

How Trump Aims To Slash Federal Support for Research, Public Health,...

How Trump Aims To Slash Federal Support for Research, Public Health, and Medicaid KFF Health News

CEO to oversee college sports rules enforcement after House v. NCAA...

CEO to oversee college sports rules enforcement after House v. NCAA settlement is finalized, per report CBS Sports

Racine LGBTQ center abruptly closes; staff seeks clarity – FOX6 News...

Racine LGBTQ center abruptly closes; staff seeks clarity FOX6 News Milwaukee

How proposed CEO could dole out punishments in college sports –...

How proposed CEO could dole out punishments in college sports ESPN

The Hollywood Reporter, GLAAD to Celebrate Pride ’25 and the 40th...

The Hollywood Reporter, GLAAD to Celebrate Pride ’25 and the 40th Anniversary of the LGBTQ Advocacy Organization The Hollywood Reporter

For the first time, the U.S. is absent from WHO’s annual...

For the first time, the U.S. is absent from WHO's annual assembly. What's the impact? NPR

Social Equality Ministry requests logo removed from LGBT advertising – The...

Social Equality Ministry requests logo removed from LGBT advertising The Jerusalem Post

Russian court fines Apple for violating ‘LGBT propaganda’ law – Reuters

Russian court fines Apple for violating 'LGBT propaganda' law Reuters

Johnny Mathis, the queer trailblazer and global superstar, takes a final...

Johnny Mathis, the queer trailblazer and global superstar, takes a final bow Advocate.com

Russian Court Fines Apple for Violating ‘LGBT Propaganda’ Law – The...

Russian Court Fines Apple for Violating 'LGBT Propaganda' Law The Moscow Times

PCUSA to require clergy candidates to be asked their stance on...

PCUSA to require clergy candidates to be asked their stance on LGBT issues Christian Post

New pope shares thoughts on gay marriage, abortion – LiveNOW from...

New pope shares thoughts on gay marriage, abortion LiveNOW from FOX

Cops arrest four for robbing men after trapping them on gay...

Cops arrest four for robbing men after trapping them on gay networking apps Hindustan Times