Gay Pride Month isn’t a thing in women’s prison — even though prison is filled with queer women – NBC News

When I was in prison, we relished things we could celebrate. There were the obvious ones — like releases and legal victories. And the traditional ones — like New Year’s Eve and Fourth of July. We also celebrated Labor Day and birthdays and the Super Bowl and holidays for religions we didn’t even believe in.

But we did not so much as acknowledge Gay Pride Month.

Queerness, like a lot of things behind bars, carried extra risks.

The presence of homophobia in men’s prisons is a known problem. But in the women’s lockups, it was completely different. In fact, women’s prison was the queerest place I’ve ever been — we just didn’t celebrate it. That’s because queerness, like a lot of things behind bars, carried extra risks.

That realization was a surprise for me, too. It was just a few weeks after I’d been arrested in December 2010 with a Tupperware container full of heroin. I was awaiting sentencing in an upstate New York county jail when the facility’s one openly lesbian guard pulled me aside to warn me: The higher-ups thought I was “too close” to my cellmate, who had become a good friend. Don’t sit next to each other on the bunk, the guard advised. Otherwise, we might get separated or transferred to another jail. We were annoyed at the assumption that any strong bond between women was somehow a cover for sex. But we were both scared enough to take the advice without asking questions.

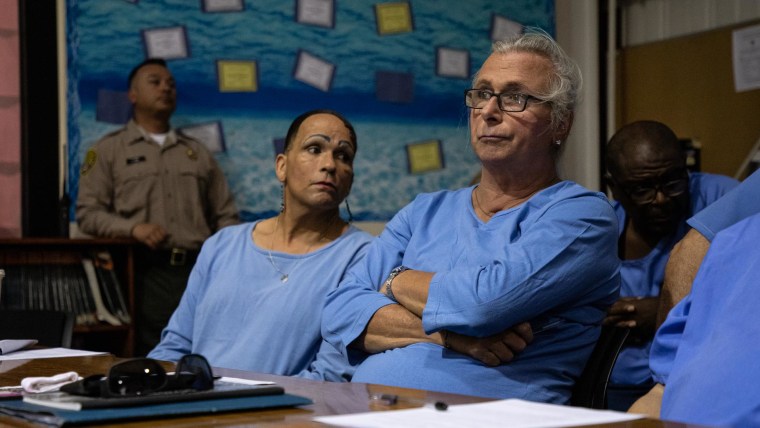

A few weeks later, I was sentenced to 2.5 years behind bars, and eventually went to state prison where the staff seemed even more invested in “catching” people being gay — which was not that difficult because so many people were. Research shows that 1 in 3 women in prison identify as lesbian or bisexual. But in New York women’s prisons, it seemed like the real numbers were much higher.

That’s because a lot of the people in New York women’s lockups had prison girlfriends, even if they had identified as straight in the free world. The shift was so common we even had a catchy phrase for it: “Gay for the stay, straight at the gate.” Sometimes those prison relationships were in addition to a boyfriend or husband on the outside, and sometimes they weren’t. Sometimes they mostly resembled a close platonic friendship with a different label, and sometimes they turned into torrid affairs that led to sex in the rec yard port-a-potties. Most ended when one person got transferred, but some outlasted prison by years.

I didn’t consider myself gay for the stay because I already identified as queer before my arrest. But over the 21 months I was locked up, I dated two women. We went to the mess hall and gym together, passed notes when we couldn’t meet and sometimes made out in closets or bathroom stalls.

On some units, the staff made it a mission to zealously police any such activity, and we had to emphasize our supposed straightness lest we become targets.

But even that kind of PG contact was a risk. Though sex with other prisoners was against the rules, so was hugging, holding hands or kissing. On some units, the staff made it a mission to zealously police any such activity, and we had to emphasize our supposed straightness lest we become targets for added scrutiny.

Not surprisingly, research shows queer people in women’s prisons are far more likely to spend time in solitary than straight prisoners. After all, if you got caught showing any sort of same-sex affection, you could get written up and punished with anything from a loss of phone privileges to weeks in isolation, and the sort of negative disciplinary record that left you less likely to make parole.

In theory those sorts of regulations were not inherently homophobic, and would just make it harder for prisoners to get away with sexually exploiting each other. But even the name both prisoners and staff used for the kind of disciplinary ticket you’d get reeked of stigma: Sexual transgressions were known as DGs — short for degenerate acts.

To some extent, I think we bought into that sort of institutional bigotry. Even though so many of us had girlfriends, being labeled “gay for the stay” carried a bad connotation. Some people who didn’t have girlfriends openly looked down on those who did — as if we were all just sex-starved deviants willing to risk our freedom for foolish things. (There’s probably a lengthy aside that could be made here in terms of the prevalence and stigma of biphobia in prison specifically.)

When I was writing this, I called one of my friends from prison to talk it through. Stacy pointed out that when women got caught having sex with male guards, they’d get isolated ostensibly for their own protection — and we’d all feel sorry for them. When they got written up for hooking up with a girlfriend, we had no such sympathy.

“There was no greater shame than getting a DG,” she confirmed. “You definitely internalize that.”

Even though we were gay, there was no pride.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about that a lot. When I read about book bans and “Don’t Say Gay” laws, I wonder what the downstream effects of such institutionalized bigotry will be. Already, it seems, I’m beginning to see them.

Over the past few months, for instance, I’ve been hit with hundreds of homophobic slurs and insults online — a volume of internet bigotry I’ve never gotten before, almost all in response to social media posts. To be sure, I know that queer people of color and trans folks in my position would face far more vitriol. And so far none of it has been enough to make me fear for my safety. But lately I’ve found myself questioning whether I look too queer in certain settings — both online and where I live now, in Texas. And when I think about the last time I had to ask myself that question, it’s a quick answer: It’s when I was in prison.