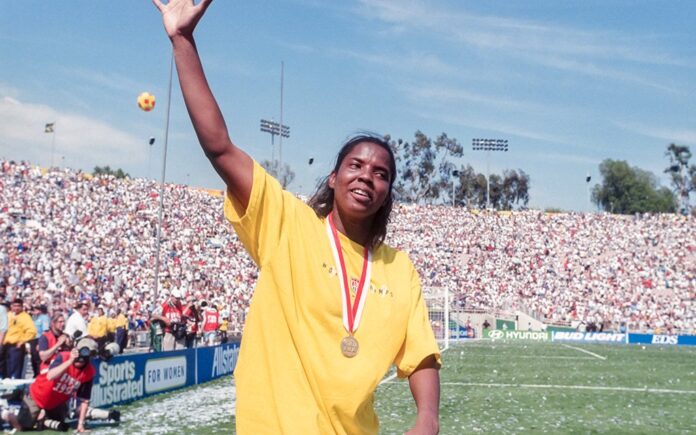

Two-time Olympian and World Cup champion Briana Scurry helped start the fight for equality in women’s soccer. Despite her accomplishments, she said, “Part of my journey was impeded by the color of my skin.” (Photo by David Madison/Getty Images)

TEMPE — “More is possible” were the words printed on Victoria Jackson’s shirt as she welcomed guests to the recent Title IX and Global Football event. On the back of the shirt were the 37 words of the Title IX law.

“No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any educational program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Dressed for the occasion, Jackson hosted ASU’s Global Sport Institute and organized a panel event to celebrate Title IX and women’s soccer. The “More is Possible” event highlighted the fight for equality in women’s soccer and the issues that are still present in women’s sports more than five decades after those words were signed into law.

“This year is the 50th anniversary of Title IX, which is the US law that has had an impact and influence globally, inspiring women to demand equal treatment on sporting fields and equal pay also,” said Jackson, a sports historian and ASU professor. “And that legacy really starts with this law in the context of women’s soccer.”

Two-time Olympian and World Cup champion Briana Scurry, who attended the event, helped start the fight for equality in women’s soccer. Scurry and the United States Women’s National Team in the 90s demanded equal rights and equal pay by boycotting the first Olympic Games that featured women’s soccer as part of the competition in 1996. The team eventually participated and won the inaugural gold medal for women’s soccer but only after the Federation offered better contracts.

Scurry’s documentary based on her life, The Only, depicts all the behind-the-scenes struggles of the national team. It reveals all the different layers of the team beyond the pitch.

“When you come out to see the women’s national team player, you come out to see any high-level sports team play, you see that one image of that game,” Scurry said. “But I think my documentary shows you that there’s so much more that goes on in how a team or a person gets to a pinnacle.”

The women’s team started the fight for equal pay and 26 years later it finally was won. Scurry and her team gave the current faces of the women’s national team the courage to continue the fight. In September, the U.S. national teams formally signed a new collective bargaining agreement that included equal salaries for the men and women.

The issues Scurry faced were not limited to her gender.. Scurry also faced inequalities due to race and sexual orientation.

“Racism is essentially woven into this country in a lot of ways,” said Scurry, who is Black and openly gay. “And that part of my journey was impeded by the color of my skin. And I didn’t want to believe that, and I didn’t want to think that that was happening. But I realized it, it took me a while (to realize) the fact that I was gay was also woven in there somehow. And I didn’t want to believe that either.”

Although the event, Title IX and Global Football, celebrated just how much women’s sports have changed, it also highlighted the need for even more improvement. With the National Women’s Soccer League reports of abuse, sexual misconduct and verbal abuse being released recently, the fight for a change continues for women’s soccer.

“I think that the league needs to have a complete revamping, I think what the report shows is that there needs to be change at the systemic level,” Scurry said. “All the teams right now just need to continue to come together, the players need to and the fact that they have a Players Association now, a collective bargaining agreement, they have a new policy in place. I think it’s going to definitely be better in this situation with the report.

“If it doesn’t destroy the league, it will definitely make it stronger. And sometimes you need a reckoning. And that’s exactly what the report was.”

Despite the challenges that still lie ahead for women’s soccer in the United States, Title IX continues to provide opportunities for girls and women that other countries lack.

A structured path to play soccer wasn’t established in Mexico while ASU soccer player Alexia Delgado and former Mexico national player Paola Lopez Yrigoyen were growing up, and both players didn’t have women to look up to to make a change.

“You didn’t really aspire much in Mexico,” Delgado said. “The biggest thing you could aspire to was to play for the national team. And other than that, for me, it was like coming to the United States and playing college and getting my education. So that was kind of like a dream for me to come here because we didn’t have a league and we didn’t have anything to look forward to.”

Added Lopez Yrigoyen: “When I was a kid, there wasn’t a guarantee, an equal division of resources for women to play soccer. Not in college, not in schools and not in professional.”

Title IX paved the way for Scurry to pave the way for the next generation of the women’s national team. More is still possible for women’s soccer and although Title IX started the fight, it’s far from over.

“Without Title IX, I’m not here with you at all,” Scurry said. “When I was younger, in high school and junior high school, universities were using soccer as the qualifier for the equity part. I became one of the first five Nike girls because I just happened to be there at the exact right time. Title IX was the best ally I could have ever possibly gotten.”