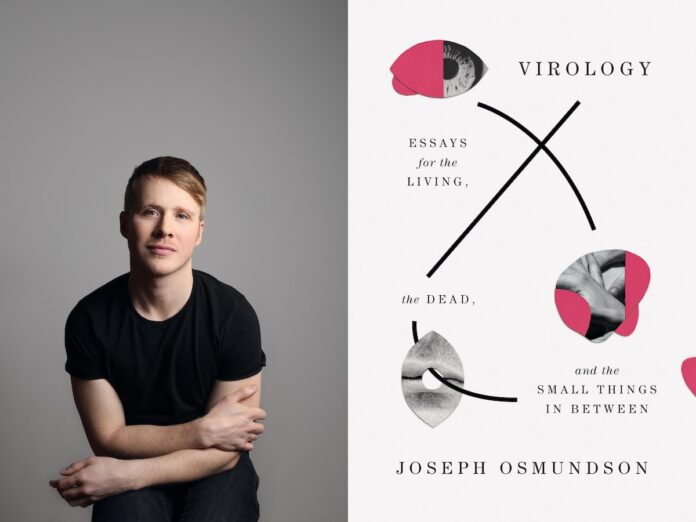

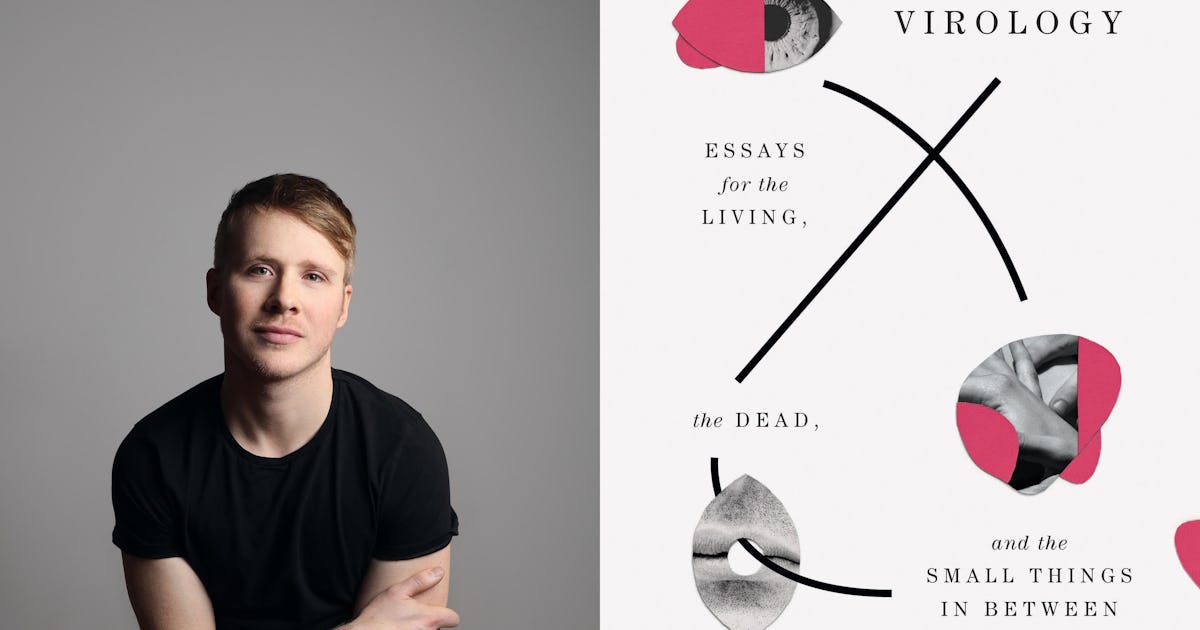

Joseph Osmundson wants us to stay curious. If you’re always on Twitter like me, this just might be a healthy antidote to hot takes and misinformation. When reports of monkeypox in the U.S. began cropping up in May, I found how badly I needed a queer voice in science to trust. This led me to Joseph Osmundson’s book, Virology: Essays for the Living, The Dead, and the Small Things in Between.

Osmundson is a microbiologist and writer, unafraid to lead, advocate, examine the self and our systems, from capitalism to whiteness, and decode how both hamstring efforts towards meaningful social change. Or how the language of war — the norm for press briefings and think pieces alike — further stigmatizes people afflicted by viruses. Through queer theory, cultural criticism, and biochemical data, Osmundson imagines a language that can encompass healthier, adaptive outcomes, centering care, and solidarity. His writing is honest and data-driven, compassionate and free of hyperbole: “What meaning do we give to a virus?…They are not evil, they don’t invade. They just are. They are a sack of membrane, they are the spike proteins, they are the RNA. They’re an accident. They’re the most abundant things on earth.”

While Virology contemplates such questions in the face of HIV and COVID, Osmundson is now organizing for monkeypox; he’s given interviews on MSNBC, with WNYC, and The Intercept. He’s part of a network of queer science advocacy — a legacy that goes back to the HIV crisis–working alongside a team of activists and scientists, including Keletso Makofane, Angie Rasmussen, and leaders from ACT-UP and TAG (Treatment Action Group), to speak out for community care and apply advocacy pressure to the federal government. Together, they’re also expanding the tent from previous activist movements (ACT-UP was often criticized, Osmundson says, for being primarily composed of well-educated cis gay white men) and centering friendship and community in their work. Within this work, he wants to reiterate that “queer pleasure–sex–is worth advocating for. Not every queer person loves sex, but many people do. And in a world that is making it increasingly difficult to live with queer and trans abundance because of literal attacks on our lives and ways of being, we cannot capitulate on sex and pleasure as fundamental to who we are and want to be.”

Now three months out from the release of his book, he spoke with NYLON about what’s changed since Virology’s release, Judith Butler, queer friendships, and prioritizing a language of care.

The New York Times says you write with the “voice of that teacher who makes science cool, even radical.” How were you able to translate the sciences so well for the general public? What did writing this feel like?

I can say from my student evaluations that not all my students think that I’m cool. I laughed at that line because of how untrue it is. It was very important to me that the science in this book be in depth. Viruses are nuanced, biological entities that one has to understand certain things about: DNA viruses versus RNA viruses? That’s the difference in genome structure at the level of a two prime hydroxyl. So I tried to introduce the notion of RNA auto cleavage via a two-prime hydroxyl, which sounds like and is a bunch of science jargon no one else would understand, in a way that feels poetic and emotional and invites people in.

I would say if it’s successful, it’s in large part due to the help of my good friend Ngofeen Mputubwele, who’s in the book, who is an artistic partner of mine, and who, especially with the science stuff, was my first reader and would always ask questions or just be like, “This makes no damn sense to me.” That’s the hard part; when I put something down on the page and it makes sense to me, I have no idea if it’s going to be something that makes sense to people without the expertise. One of the notes from Mo [my editor] on a draft of the science essay at the beginning of the book was like, “I hate biology, but I like this.”

In Virology, you write to illuminate the sciences. How do these two parts of your career inform your thinking about the other?

Science obviously informs my writing. If I’m going to sit down as a queer person and write about the experience of having lived with HIV in the world for my whole life, and how it feels to have sex with the fear of [HIV] always present, of course, to me, as someone who literally did experimentation on retroviruses related to HIV as an undergraduate researcher, that of course colors my understanding of the virus. I think my brain is a scientist’s brain, and I will never be able to take that out of my writing. At first, I didn’t want to write at all about science because I wanted to be able to write about whatever I wanted. But as I got more secure as a writer, I allowed that more obviously to come into the work, which was the right choice; it’s a part of who I am.

One of the core ideas of the book is how we use language and metaphor, whether revisiting Susan Sontag or analyzing the government’s talk about the war on COVID. You also talk about the importance of care for each other. How do these kinds of care refract off each other and operate together?

My stress relief in these very stressful times is to come home to cook a fancy dinner. Last night I was making a bougie version of chicken marsala, where I did homemade pasta, and a bunch of different preparations on the meat, and I was listening to a Judith Butler lecture on language as performance and its relationship to gender.. Judith argues that we obviously use language, but language is done to us before we ever use it. We learn language, and language has certain constraints on it, particularly around gender. Language uses gendered pronouns. And so, if you’re trans, Judith was arguing that one of the first things gender ever does to you is call you a name that you don’t accept as your own: the gender pronoun. It’s this very complex relationship about what language does to us, how we use language, and then how language can actually create different worlds. I think it’s the last one that has been on my mind so intensely. I [wrote] an essay about journalists using what I consider really harmful language around monkeypox. One thing that Sontag argues is that being ill is enough suffering; we don’t have to use poor metaphors of illness to increase the suffering of people who are already ill.

When you say something like “gay sex fuels monkeypox,” you’re not pointing at systemic failures, you’re not pointing at the fact that my friend tried to get vaccinated and could not get vaccinated, had a hard time getting testing, had a hard time getting treatment —it took him ten days after his test to get treatment — you’re pointing back to the individual behaviors as the cause of an epidemic, and that is part of why my friend felt bad. It is doing material harm to the mental health of people who are already isolating for a month plus with a very painful virus. The epidemic is being fueled by global post-colonial racism, because we didn’t care to vaccinate people in Nigeria in 2017 to now, and being fueled by a global lack of access to vaccines. That doesn’t mean we’re not being honest about the virus transmitting through fucking. The virus has transmitted mostly through sex. But the words you choose, actively choose, because when you speak you are making action with language, and that action has an inherent value. My whole book argues that it is essential to choose the value rooted in care.

“I think my brain is a scientist’s brain, and I will never be able to take that out of my writing.”

Another form of care in your book comes through queer friendship, whether your podcast or with the writer Alexander Chee. Can you speak to the power of queer friendships and telling stories about it?

There are a lot of things that I can say better than Foucault — you know anything on race, for example — but on queer friendship I think Foucault does have the framework that I always go back to. He talks about queerness not as a form of desire, but as something desirable. It is good to be queer because of the way we make friends.

When we look at the ways that capitalism atomizes us, we are expected to build little family units. My parents both were incredibly far from all of their family members. I had no aunties or uncles in my life on a day-to-day basis. They made friends with some of the neighbors who had kids for mutual care, but it’s not like they actually felt like an auntie, or an uncle, or a co-parent, or anything else. That fucking sucks. That is not a nice way to raise children, and it is a relatively novel invention of American capitalism — and capitalism elsewhere — to expect people to do this. It’s lonely. It does not put friendship as a core tenant of life.

When I finished grad school and I stayed in New York as opposed to moving to Chicago, where my number one job was, I had just gone through a really horrible break-up, and I could feel all the judgment of all the straight people in my life being like, “You don’t have a partner. Why don’t you just move to Chicago?” I couldn’t express it this way at the time, but I was staying for my friends, and it was completely a decision that I felt self-conscious about. As I approach 40, I can now look back and say that decision was right for me. I’m glad that I prioritize friendship in my life.

One other thing that Chee told you is that “gay writers need to allow themselves to be self-indulgent, to get over our fear of being read as dramatic.” You embrace this at the end of that essay. What has become possible as you’ve allowed yourself to indulge?

It’s a lifelong journey of undoing internalized homophobia: how I hold my body, what my voice sounds like, that I was literally beat as a child by other children for being effeminate. That is my lived experience, and that will never go away. Just like language is done to us, so is gesture, so is how I hold my body, who I touch, and how I touch them. Being able to physically touch my male friends, especially since I was socialized as a guy and had a huge prohibition on the vast majority of types of nonviolent male-male physical connection, it feels electric to be able to touch my friends in intimate ways. To be soft with other people who are boys or trans folks. To have gender not be a violent line that draws who I can touch safely, and who I can’t. I think that it works at every level from our private lives–how I hold my body, how I talk to my friends–to the risks we’re willing to take in our art.. It’s a lifelong project that is not divorced from gesture and community and who we are as a person.

In a COVID diary on March 9, 2020, you wrote, “We need to have the conversations that our elected leaders are not. We–queer people–need to know the risks of our events and gatherings, that they might harm us or those close to us.” What questions do you think queer people should continue asking in the face of this monkeypox outbreak, and future outbreaks?

What you said about my book–how you received it and it was calming–makes me really, really happy, because my book does not shy away from the horror of HIV or COVID-19, but it tries to talk about things without hyperbole, to give information as accurately as possible, but also acknowledge that science is a methodology where our understanding constantly changes thanks to shifting frameworks and new methodologies. I tried to write about it in a way that was curious. I think curiosity, in a way, helps calm because you’re not getting shouted at a bunch of facts about how the world is going to end, you’re learning. You’re learning what viruses are and how we live with them while minimizing harm. The relationship that I was talking about on March 9 initiated a long-time partnership that isn’t in the book because it mostly occurred after that essay.

I described this phone call that was very tense between me and a promoter of a party where people have sex. I was real with them and said not just, “I think you should close down now,” but, “Y’all need to get ready, because when you close, it might be six months or a year, and I know that you’re financially precarious in that situation.” Because of the way that I talked to them, when that ended up happening, it built a huge amount of trust, I think mutually. Because a lot of the people who go to places where people meet for sex were disproportionately impacted by monkeypox early on, those spaces made the decision by themselves to stop their parties and to become a place where people learned. A whole bunch of folks who run nightlife and sex spaces were reaching out to me to help them craft language that would get information out to their communities. That, I think, is exactly what should be happening. It’s all within the queer community.

[Someone] in the leather scene [told me], “We know people who are not talking honestly about this to their doctors, but the sweat in some of the leather gear transmitted the virus,” and I said, “Oh, that makes perfect sense based on all the science we know.” It helped me to hear from them, to bring that back to the folks working on the science. Information comes from community, and then we also help inform the community with our expertise. It’s just so queer. I feel like I’m doing science with this person who hosts a leather party, and that person has done a huge amount of literal epidemiology because they’ve talked to fifty people across the nation in this trusted community.

It is essential to say our scientific knowledge of monkeypox will change. It will change. We will learn how effective the vaccines are. We don’t yet know that exact number. Inviting people to be curious, to be knowledgeable, not to shout at them “science facts.” Science doesn’t have facts; it answers questions. I think the more honest we are with that process, and the more mutually we view our expertise informing community and community informing our expertise, the better off we will be long term.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.