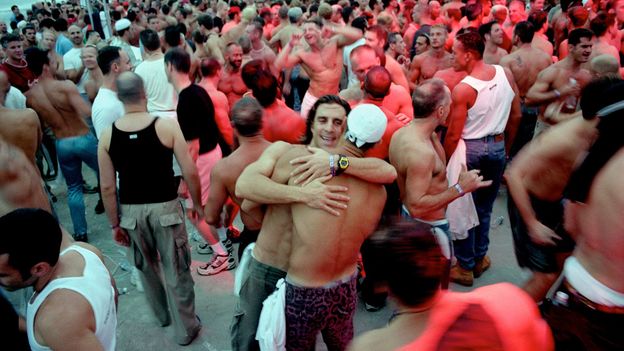

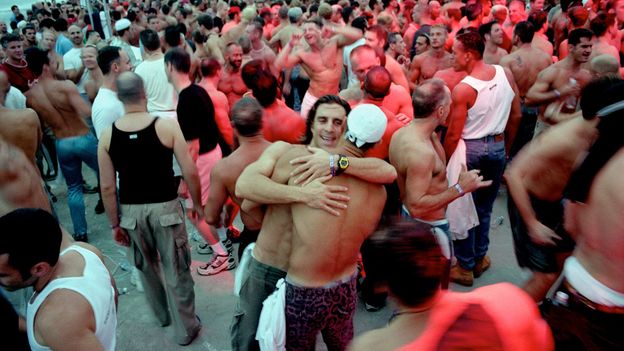

Going into the post-war period, Cherry Grove became increasingly well-known as an eccentric, outrageous spot, its small-town atmosphere enriched with a vibrant theatrical and drag culture, and ample venues for drinking, dancing and public sex. The Grove’s more upmarket neighbour, Fire Island Pines, was developed later, in the 1950s, as a “family-friendly” community, although this label didn’t last for very long, despite the fact that numerous gay homeowners had moved there from the Grove in the hopes that it would act as a more discreet enclave. By the 1970s, with the flourishing of an increasingly public queer culture in the years following the Stonewall riots, Cherry Grove and the Pines were both highly desirable locations, frequented by writers and, including Truman Capote, James Baldwin, Patricia Highsmith, Carson McCullers, as well as numerous stars of stage and screen. That the supposed golden age of Fire Island’s loose and liberated culture was so short-lived, before the HIV/Aids epidemic began decimating its community in the early 1980s, only further informs its mythology as a fragile, sacred place, lingering defiantly on the fringes of the Atlantic.

A place of “death and desire”

Because here’s the other thing about Fire Island; it is a haunted place. It is, as WH Auden writes in his 1948 poem about the place, Pleasure Island, as if the “lenient amusing shore / Knows in fact about all the dyings”. As much as a summer on Fire Island is about immersion in the present moment (this weekend) or the near future (this season), the past is never far away. Scratch beneath the glamorous, hedonistic sheen of its popular image and a rich cultural lineage comes into view, along with the ghosts of the various figures who have graced its shores. Before I began research on my book Fire Island: Love, Loss and Liberation in An American Paradise, which examines the queer cultural history of Cherry Grove and the Pines, while interweaving aspects of personal memoir, I went there in the spirit of pilgrimage, seeking to retrace the footsteps of poet Frank O’Hara, who was killed on the beach near the Pines in a dune buggy accident in the summer of 1966. Standing by the ocean in the early hours of the morning, incanting lines from one of O’Hara’s poems, the deathliness of the place became vividly apparent; the sense that it is teeming with the life (or lives) of its past. As the narrator of Andrew Holleran’s classic 1978 novel Dancer from the Dance notes, this is a place of “death and desire”.