Seventy-six years after the United States dropped nuclear weapons on two Japanese cities, World War II historians still hotly contest president Harry S. Truman’s decision to drop atomic weapons on civilian populations.

Japan was stubbornly refusing to surrender in the summer of 1945 despite suffering crippling blows in battles with Allied Forces in the Pacific theater. “Operation Downfall,” a plan to force a surrender by invading and occupying the country, would require 1.7 million U.S. troops, according to U.S. War Department estimates. The invasion would have resulted in 1.7 to 4 million U.S. casualties, including 400,000–800,000 dead, and 5–10 million Japanese dead, according to military leaders at the time.

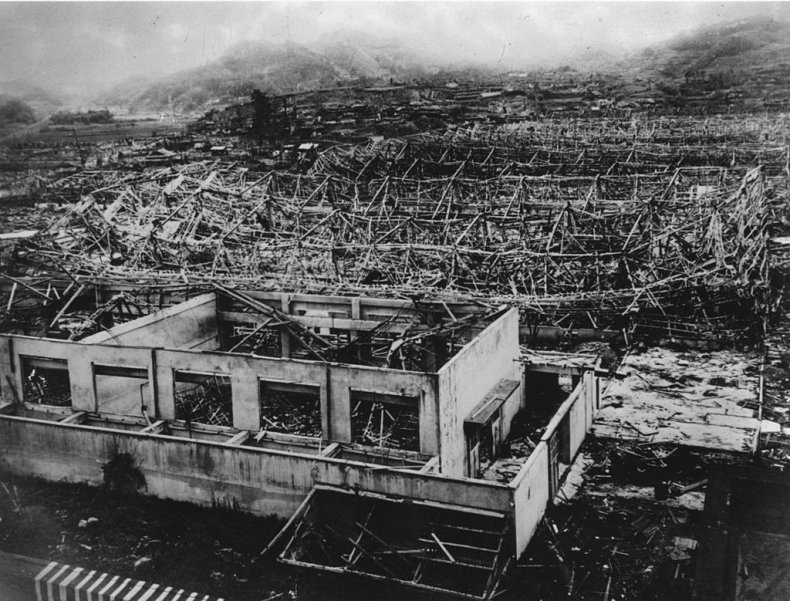

Hiromichi Matsuda/Handout from Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum/Getty Images/Getty Images

Truman learned of America’s effort to develop an atomic bomb only after the death of his predecessor Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He ordered the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on Aug. 6 and 9.

Determining the death tolls in Hiroshima and Nagasaki has been difficult, because injuries and radiation exposure killed people for years afterward.

The U.S. Department of Energy estimates that 70,000 people, mostly civilians, died in the initial blast when the Enola Gay, a B-29 bomber, dropped the “Little Boy” bomb on Hiroshima. The death toll likely climbed to 100,000 by the end of the year, and related deaths after five years may have pushed the total to 200,000 as long-term effects of the radiation emerged.

When “Fat Man” flattened Nagasaki three days later, according to a Department of Energy estimate, the initial blast killed 40,000 and injured 60,000 more. The five-year death toll may have reached 140,000.

The death and destruction was not out of proportion with aerial bombing campaigns that had already been raging for three years, including those carried out by the United States. “Operation Meetinghouse,” the fire-bombing of Tokyo by U.S. Army Air Forces on March 9, 1945, had a higher immediate death toll and destroyed more territory than the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Getty Images

But the atomic radiation’s lasting effects, and death tolls that kept growing, set the two apart from other bombing campaigns.

“No one knew,” said Thomas Sutton, a political science professor at Baldwin Wallace University whose parents both worked on the Manhattan Project.

“There were all kinds of hypotheticals, and they certainly knew about the effects of nuclear-induced illness from other experiences, ” he told Zenger, “but the mass scale and lingering effects — it was hypothetical versus seeing it happen.”

Experts remain split on whether Truman’s decision to drop the bombs was the right move. Sympathetic historians cite the need to preserve American lives and bring a swift end to the war. But that’s not a universally held view.

“This is an issue that has been debated and discussed for 70-some years,” Peter Bergerson, political science and public administration professor at Florida Gulf Coast University, told Zenger. “One of the first things that I think about is that with every decision of the government, there is an ethical component or an ethical aspect to it. And in hindsight, this is what we’re seeing.”

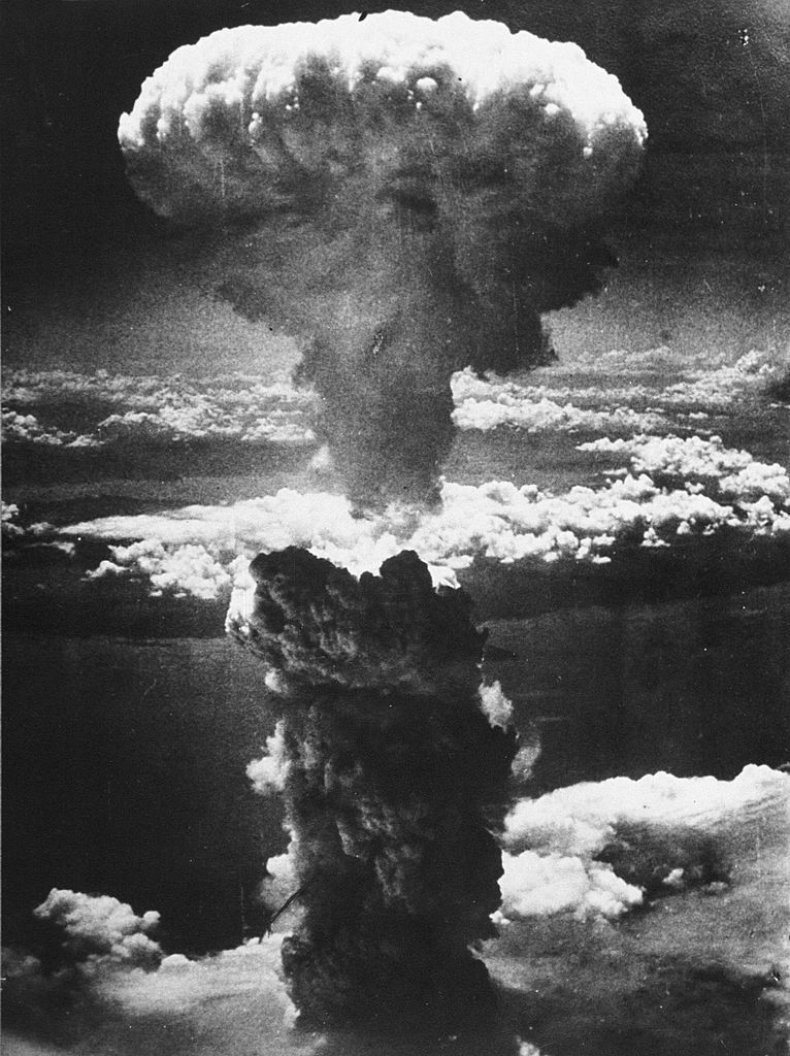

Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

“The total American lives lost in World War II was somewhere in the neighborhood of 270,000,” said Sutton. “So when you’re looking at a casualty count of three or four times that number … you can certainly see where the military would say, ‘Well, let’s give this bomb a shot.’ In hindsight, that was necessary at the time to end the war and keep at a minimum the casualty count.”

Japan’s surrender after the Nagasaki attack proved the bombings accomplished what Truman wanted them to, Bergerson said. Japan had resisted surrender despite a crippled navy, a lack of fuel and a U.S. submarine blockade cutting off food to the home islands. But the twin mushroom clouds changed everything.

“The president made the decision that this would shorten the war, this would save American lives, and he went forward with that decision,” said Bergerson. “The downside, obviously, was the horrific damage that was done to noncombatants. It’s a hard call. This is one of the decisions that presidents have to make. … It certainly hastened the end of the war.”

But some scholars say atomic weapons weren’t necessary to win the war—that in fact the threat of invasion would have led to the same result. And others credit Soviet leader Josef Stalin, not President Truman, for putting the white flag in the Japanese emperor’s hand.

Ward Wilson, author of 5 Myths About Nuclear Weapons, told Zenger “there’s no question” it was the Soviet Union’s declaration of war that led to Japan’s surrender.

“The Soviet entry into the war around midnight on Aug. 8 is what triggered the Japanese Supreme Council to meet. It’s what encouraged one of the higher military commanders to urge that they kidnap the emperor and set up a military government. It caused all the military leaders to meet in an emergency session in Tokyo, and none of those things happened right after Hiroshima was bombed,” he said.

Courtesy of the National Archives/Newsmakers

“If the atomic bombing were going to cause Japan to surrender, there would have been all these emergency meetings and these plans to overthrow the emperor on the day that Hiroshima was bombed or at least the day after,” he said. “But Hiroshima was bombed on Monday, the 6th, and by Wednesday or Thursday, they’re still not acting as if it’s a crisis. Then overnight, the Russians declare war, and everything changes.”

The argument that the bombings caused Japan to surrender rather than the Soviet declaration of war and invasion of Japanese-occupied Manchuria has fostered “this whole mythology about Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” said Wilson.

“The myth still kind of exists in the public, but the academic world is starting to draw back and say, ‘Well, it was the Russians and the bomb.’ Partly because the Japanese told us they surrendered because of the bomb,” he said.

“It was the perfect excuse for why they lost the war. Instead of saying that the other side was smarter and better, and they fought harder and were braver, you could say, ‘Well, the other side made an incredible scientific breakthrough, and that’s why we lost.'”

Wilson also said what he called the “saving lives argument” doesn’t hold water.

“It’s not really an ethical comparison because what you’re doing is you’re killing civilians in order to save soldiers,” he said. “And soldiers, they know what their lot in life is. Their job is to fight and die. But civilians in theory shouldn’t imagine that they have to die in order to protect their country.”

Truman may not have had much choice. He was kept in the dark about the Manhattan Project despite being Vice President of the United States. Developing nuclear weapons came with a $2 billion price tag, about $30 billion in today’s dollars. A targeting committee had already laid out plans for where to drop the bombs, leaving Truman with few options after FDR died.

Keystone/Getty Images

“It would have been a really tough call to be a brand-new president and to come in and say, ‘There’s this program that we’ve spent a ton of money on, and everyone thinks it’ll win the war,’ and you’re going to say, ‘No,'” Wilson said.

Truman’s decision continues to be the stuff of academic second-guessing.

“It’s almost like the chicken and egg argument,” Bergerson said. “Does the end justify the means or do the means justify the end? And here, clearly is the perfect example of an incident in which the means — dropping the atomic bombs on Japan — are they justified?”

“As we evolve in historical reflection, we raise these ethical issues. Was this something that we should have done or not? There’s no easy answer,” he said.

This story was provided to Newsweek by Zenger News.