Illustrations by Zakye Rothmiller

A lot of historic events have taken place around the Main Line, but these six curious tales won’t be found in any history book.

Backstories are backstories for a reason—and they were the focus of my Retrospect column, which ran monthly in Main Line Today from 2003 to 2019. One that really stuck with me was the tale of Nathaniel Wyeth, which is included in this collection. An engineer who spent his career with DuPont, he invented the plastic soda bottle in 1973. I found an exquisite irony in the fact that the brother of Andrew, an artist famous for his depictions of unspoiled landscapes, was also the person perhaps most responsible for marring those scenes (and many others). It’s not a story you’ll hear at the Brandywine River Museum of Art.

Another of my favorites didn’t make the cut here. It’s the story of Phillis Burr, whose rage practically screams off her tombstone at Great Valley Baptist Church in Devon. Likely born in Guinea, Burr was kidnapped into slavery in 1800. In the “white” narrative, she was rescued by the U.S. warship Ganges, which seized the American-owned slave ship carrying her to market in Cuba. Slavery was still legal at the time, but slave trading with U.S.-flagged vessels was not.

The Ganges’ captain sent Burr’s ship to port in Philadelphia, a city with strong anti-slavery sentiment. But returning her to Africa was not in the cards. Instead, the 10-year-old Burr was signed to an indenture with John William Godfrey, a Philadelphia ironmaster who promised she’d learn “housewifery” and receive an education in exchange for eight years of labor.

Many white Philadelphians were proud of their roles in keeping free those intended for slavery. But the reality was that these unfortunate souls never again saw their homes and were assigned to unpaid labor. Burr’s attitude is reflected in her epitaph: “Brought to America in the warship Ganges and sold into slavery to pay for her passage.”

There is, remember, always another point of view.

Trust No One

There are few unmixed blessings. This was especially true 150 years ago, when “In God We Trust” was first placed on United States coins at the suggestion of a certain Delaware County minister. Looking back, one must embrace the circumstances under which it was done. It was a package deal—one of national devastation and 750,000 dead. It was all about religion.

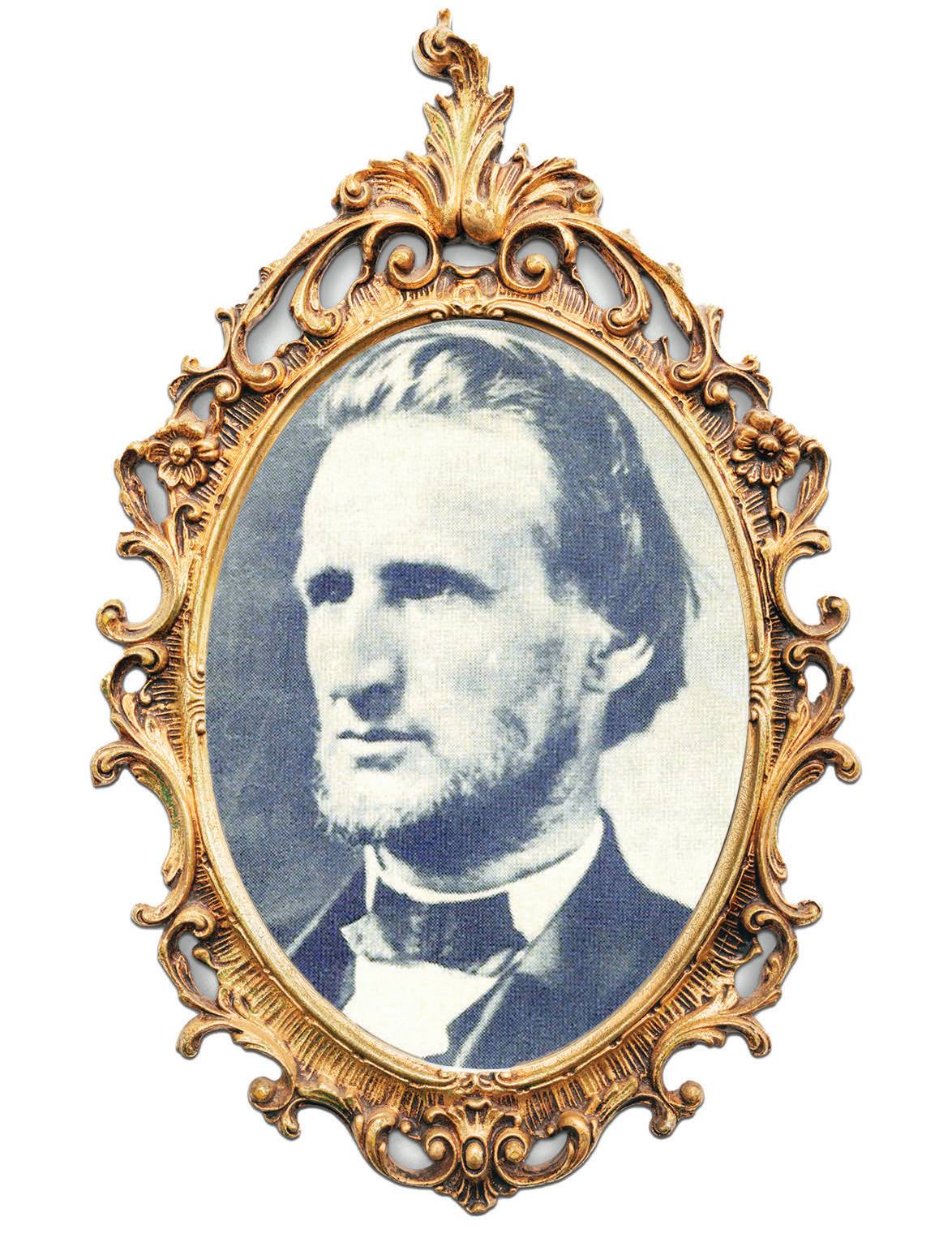

In 1861, Reverend Mark R. Watkinson was pastor of Ridleyville’s First Particular Baptist Church (now Prospect Park Baptist). That year, he wrote to Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase. Fort Sumter had fallen, and Union forces had been defeated at First Bull Run. Prospects for restoring the country seemed dim.

Reverend Mark R. Watkinson

Watkinson’s remedy: Add the words “God, Liberty, Law” to the national coinage. “You are probably a Christian,” he said to Chase, asking how the United States would be remembered if Confederate secession was successful. “Would not the antiquaries of succeeding centuries rightly reason from our past that we were a heathen nation?”

Chase bought the logic, if not the wording. Raised by Episcopal bishop Philander Chase, he’d made a name for himself applying his religious views to the cause of abolition. Before joining the Lincoln cabinet, Chase regularly defended runaway slaves, and the white citizens who helped them, while denouncing fugitive slave laws. Within the week, he wrote to James Pollock, director of the U.S. Mint. The director of the mint was, according to his 1890 obituary, “always eager to do the Lord’s business.” Other than his proposal to the treasury secretary, Watkinson left remarkably few historical footprints. He was born in New Jersey and prepared himself for the ministry at the University of Lewisburg (now Bucknell University) and Columbian College (now George Washington University). He was active in the American Baptist Missionary Union.

In 1850, Watkinson was living in the Spring Garden section of Philadelphia. He came to Ridleyville the following year, and he seems to have remained at First Particular until about the end of the Civil War.

As for the wording on the coins, Congress gave the treasury secretary carte blanche. “In God We Trust” fit best. The phrase went first on one- and two-cent coins, and eventually on everything. In 1956, during the Cold War, Congress passed a joint resolution that made it the official national motto, also adding it to paper money.

By the time the phrase first appeared on coins, however, evangelical political fervor was falling out of favor. The carnage of war had made Americans more skeptical of evangelical enthusiasms. In 1861, both sides had marched off sure that God was on their side. A Louisiana woman described the conflict as “a Battle of the Cross against the modern barbarians.” In the North, thousands responded to Julia Ward Howe’s new “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” which urged Christ-like martyrdom: “As he died to make men holy, let us die to make men free.”

But, by 1864, Confederate chaplains were struggling to explain how they were losing if God gave victory to His chosen people. “At the beginning of the war, every soldier had a Testament in his pocket,” lamented one. “Three years later, there were not half dozen in each regiment.”

It was a belief that God did not, after all, have His hand in the bloody war. The soldiers, and the country, just wanted to finish the job and go home. They’d rejected the package deal.

Originally published in the February 2014 issue of “Main Line Today.”

Just Friends?

Time and circumstances change how we look at things. In the 1870s, a man who consorted almost exclusively with other men—traveling and sleeping with them, speaking of his love for them—would be about average. What choice did a guy have? Victorian convention made relationships with women formal and artificial. Only male relationships could be close and casual.

Today, though, it all seems rather, well, gay. That’s the posthumous predicament of Chester County’s Bayard Taylor. In 1870, he published the not-so-successful novel, Joseph and His Friend: A Story of Pennsylvania. Some historians have since declared it America’s first gay novel. As evidence of Taylor’s sexuality, they point to his six-year engagement to high-school sweetheart Mary Agnew. “The engagement, like all suspicious engagements, was a long one,” observed Philadelphia writer Thom Nickels. “What forced the marriage was Mary Agnew’s coming down with tuberculosis.”

The couple had only been married two months when she died in December 1850. Quite convenient—except that Taylor later remarried a woman with whom he then lived for 20 years.

Born in Kennett Square, Taylor was the product of an English-German family. His father, Joseph, was a prosperous farmer. Farming didn’t interest Taylor, so it was his good fortune when, in 1837, his dad was elected Chester County sheriff. The new job required that the family relocate to West Chester, where young Taylor attended Bolmar’s Academy, a private school probably several notches better than any available near the family farm. While studying in West Chester, he published his first article, an account of a visit to Brandywine Battlefield, in the West Chester Register. His first poem ran in the Saturday Evening Post the following year. He was just 16.

Taylor wanted to go to college, but his family had no money for that. Instead, he apprenticed for four years with a West Chester printer. He lasted 12 months, quitting when Philadelphia magazine editor Rufus Griswold suggested that he write a book of poetry. Taylor wound up selling Ximena; or the Battle of the Sierra Morena, and Other Poems by subscription. He made enough from Ximena that he could afford to buy out his apprenticeship and travel to Europe.

The European tour lasted two years. When he returned, Taylor republished his newspaper columns in book form: Views A-foot; or Europe Seen with Knapsack and Staff, written to appeal to the would-be traveler of modest means. The book sold well, and Taylor received congratulations from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and John Greenleaf Whittier, both of whom met with him on a visit to Boston. Heady stuff for a 21-year-old.

Bayard Taylor

Needing a steady income, Taylor bought a newspaper in Phoenixville. After a year, he sold the paper and moved to New York to work for $5 a week at The Literary World, the first important American weekly devoted to discussion of current books. In 1848, Taylor began a life-long association with the New-York Tribune, which soon sent him to California to write about the Gold Rush. That trip resulted in Eldorado, one of his best and most popular travel books.

Back in Kennett Square, Mary Agnew was dying. While her fiancé bustled about in New York, her life had become a search for relief from a nagging cough and physical decline. She was buried in December 1850. Eight months later, Taylor was off again, this time to the Middle East. In Egypt, he met August Bufleb, a German businessman. Both became enamored of the other. Bufleb wrote home to his wife that Taylor was “a glorious young man.” “If it were not for you, I would go with him. He has won my love by his amiability, his excellent heart, his pure spirit, in a degree of which I did not believe myself capable,” he said.

Of Bufleb, Taylor told his mother, “When we speak of parting in a few days, it brings the tears into our eyes.”

Taylor built a mansion, Cedarcroft, which still stands in East Marlborough Township, and used it to entertain lavishly. In his career, he wrote 10 travel books and was known as the “Great American Traveler,” but travel interested him less and less. Taylor’s first novel, 1863’s Hannah Thurston: A Story of American Life, is set in Chester County, which he clearly loved, though with mixed feelings.

Taylor’s opinion of women seems to have declined still further by the time he published Joseph and His Friend in 1870. It’s prefaced by a dedication to “those who believe in the truth and tenderness of man’s love for man, as of man’s love for woman.”

The novel was not popular, and Taylor’s defense of the book was mostly muted. “What I attempted to do,” he wrote, “was to throw some indirect light on the great questions which underlie civilized life, and the existence of which is only dimly felt, if not intelligently perceived by most Americans.”

Was Taylor gay or just worldly? It’s hard to say for sure. His attitudes differed from those of his contemporaries. He was fond of the Middle East, where male friends still walk hand-in-hand in public. He was also religiously tolerant—even of phallic worship, which he said offered “profound philosophical truth.”

Perhaps he was merely a traveler who, after a long time away, returned to his native land and saw it for the first time.

Originally published in the August 2014 issue of “Main Line Today.”

The Other Wyeth

Odd pairings are legendary. There’s Bill and Hillary. Jimmy Carter and his beer-drinking brother, Billy. And then there’s Andrew Wyeth and his brother, Nat. One is an artist famed for his depictions of the parched winter landscapes of Maine and Chadds Ford. The other was responsible for much of the litter that mars those landscapes—and most others, as well.

Nathaniel Wyeth, an engineer who spent his career with DuPont, invented the plastic soda bottle. That’s the bottle, patented in 1973, whose manufacture requires 1.5 million barrels of oil annually and has only a one-in-five chance of ever being recycled.

During his career, Wyeth invented or was the co-inventor of 25 products and processes in plastics, textile fibers, electronics and mechanical systems. The third child of Carolyn and Newell Convers (N.C.) Wyeth, he was initially named for his father. But the boy’s parents went to court before he reached age 5 and had his name legally changed. It was their habit to put toddler Nat out on a sunny, enclosed porch in a baby carriage for his daily nap. But his hands were always greasy when they got him up. “One day, they kept an eye on me,” Wyeth said later. “Then they noticed me lean over the side of the coach, reach down and move the wheels with my hands.”

By turning the wheels, the little boy made the coach move from one end of the porch to the other. Back and forth, over and over, dirtying his hands in the process. “I don’t know why we should encumber this boy with an artist’s name when he’s undoubtedly going to be an engineer,” said his father. “Look at his understanding of those wheels and the way he’s moving that coach!”

So, Newell Convers Wyeth Jr. became Nathaniel Convers Wyeth, a name he shared with an uncle who was an engineer. Throughout his life, Wyeth dismissed the notion that his father might have been disappointed that he didn’t paint. “The only thing he insisted on was that whatever we did, we should do it with all our hearts, with all our might,” he said.

Wyeth earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in mechanical engineering from the University of Pennsylvania, a school recommended by another engineer-uncle, Stimson Wyeth. After college, he joined Delco, a Dayton, Ohio, auto-parts company recommended by his namesake, Uncle Nathaniel. At Delco, he made a good impression early on by solving a production problem in the manufacture of Sani-Flush, the toilet bowl cleaner. One of the ingredients kept plugging a valve in a machine that mixed the cleaner. The valve crossed from one side of a pipe to the other, but sometimes couldn’t close entirely because the gritty, acidic material was in the way. Wyeth replaced the single-gate valve with a two-door version.

That got him a promotion to Delco’s R&D lab to work on new concepts and devices. It was exactly where he wanted to be—but at DuPont, near his home. So, in 1936, as soon as an opportunity arose, Wyeth jumped ship. His first DuPont invention was a machine that filled cardboard tubes with gunpowder to make dynamite, then he moved on to plastic. Informed that it couldn’t withstand the pressure of carbonation, Wyeth wanted to see for himself. He went home, filled an empty detergent bottle with ginger ale and put it in the refrigerator overnight. The next morning, the bottle was so swollen it had become trapped. Wyeth couldn’t remove it until he’d carefully bled off some of the built-up pressure. “No wonder they don’t put carbonated beverages in plastic bottles,” he realized. “They’re too weak.”

Wyeth knew that plastic could be strong. From his experience working with nylon, he saw that the strength of plastic increased when stretched. Working with one assistant and a hand press, Wyeth produced many shapeless globs of plastic and, later, some truly ugly containers. “I remember bringing some of those samples over to my boss,” recalled Wyeth. “He’d ask, ‘Is this all you’ve done for $50,000?’”

Wyeth later estimated that he had made 10,000 attempts. Success came late in the day when the lab was dimly lit. He and his assistant opened the mold, expecting more shapeless globs of resin. Instead, the mold seemed to be empty. They looked closer and found a crystal-clear bottle. “Since then, I’ve seen countless truly beautiful plastic bottles,” said Wyeth. “But none of them will ever be as memorable as the first.”

As his final improvement, Wyeth replaced polypropylene with polyethylene terephthalate, which has superior elastic properties but is permeable to carbon dioxide over time. Put a Coke on the shelf for six months, and it will go flat. That never happened with glass. It’s why soft drinks now have expiration dates.

By 1980, production of plastic beverage bottles had exploded to 2.5 billion containers—and to 5.5 billion units by 1985. Glass became obsolete. Plastics experts predict that the PET bottle will eventually be standard for wine, liquor, beer and many other products. And, of course, for roadsides.

Years earlier, defending his son’s career choice, N.C. Wyeth had insisted, “An engineer is just as much an artist as a painter.” But the elder Wyeth—famously critical of his own work—also knew that not all art is good.

Originally published in the February 2009 issue of “Main Line Today.”

The Music Lover

Music has its charms but also its dangers. In the case of a Civil War drummer boy from West Chester, music got him killed. Charley King was 12 years old when the war broke out in 1861. Naturally, he wanted to go. He could beat a drum—and in the early days after Fort Sumter, the war was all about flags, parades and bands.

Naturally, Charley’s parents said no. But the captain of a Chester County company—a man raised with a love of music—promised the Kings he would keep their son safe. Less than a year later, after surviving eight battles on the Virginia Peninsula with the 49th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers, Charley King was killed at Antietam. He was shot as his unit sat waiting for orders. “We should be glad, if we were able, to write his epitaph,” reported the Jeffersonian newspaper. “He was a remarkable boy, and truly may it be said of him that he was not as other boys. Very young, quite small, yet manly. Kind, affectionate, quiet, trusting, yet proud and ambitious—and a superior musician.”

Born in 1849, Charley was the eldest of eight children born to Pennell King, a tailor, and his wife Adeline Bennett. His life was brief and, for public purposes, began April 14, 1861, when news of the bombardment of Fort Sumter reached West Chester. “It aroused the people of the county to a most remarkable degree,” wrote historian W.W. Thomson. “Before night of the next day, measures were taken to raise troops.”

On Tuesday, in a meeting at West Chester’s Horticultural Hall, members of what became the 9th Regiment enlisted for three months. James Givin was elected captain; Benjamin H. Sweney, first lieutenant. The unit left for Harrisburg on April 23, with Charley in tow.

It was an exciting time. In May, the Camp Wayne training center would be established at Church Street and Rosedale Avenue. Just blocks from the King home at Barnard and High streets, it was a scene of near-constant drilling. During that spring and summer, the county contributed companies to five different regiments. Troops arrived and departed with great fanfare. Charley didn’t wait around. He marched off with Givin, Sweney and the 90-day G-men in April. But only as far as Harrisburg, as his parents wouldn’t permit him to go any further.

The 9th spent its time mostly waiting for orders. Its men were discharged in July, by which time Washington figured out that an army would be needed for several years. Sweney reenlisted on July 27 and immediately began the work of organizing what became Company F of the 49th Regiment in September. Again, Charley followed. And, again, he was supposed to come home after the soldiers reached Harrisburg. Following the regiment to the front, said his parents, was too far and too dangerous for a boy of just 12.

But this time, Sweney intervened. Having seen how music can move a crowd and having undoubtedly witnessed the usefulness of a military band, he opted to keep Charley around. And while a 12-year-old in the army was not the norm, neither was it terribly unusual. Some historians believe that as many as 420,000 Civil War soldiers were under the age of 18. Because they didn’t carry weapons, the youngest were often found carrying drums.

Charley apparently did his job well. In December, when the 49th was camped about 10 miles from Washington, he’d been promoted from drummer to drum major. That put him in charge of the band and its discipline. The 49th remained near Washington until March 1862, when it was ordered to Newport News, Virginia, to take part in what came to be called the Peninsula Campaign. Richmond was about 70 miles up the Virginia Peninsula, and the Union high command’s plan was to push north until it got there. Union troops outnumbered Confederate almost two to one (120,000 to roughly 70,000), but the campaign was still a failure.

Having beaten General George B. McClellan on the Peninsula, Confederate General Robert E. Lee opted next for an invasion of Maryland. McClellan’s army—including the 49th—gave chase and found itself facing Lee’s troops across Antietam Creek near Sharpsburg, Maryland. The September 17 Battle of Antietam was the bloodiest day in American military history, with 22,717 dead, wounded and missing.

Charley died on September 20. Two weeks later, in West Chester, the Jeffersonian reported his death: “The ball, we understand, passed through his lungs, and he survived but a day or two. When his father, Pennell King, went on to take care of him, as he supposed, he found the grave only, in which his sons remains were deposited.”

Charley was laid to rest at West Chester’s Greenmount Cemetery. Sweney died in 1912 and was also buried at Greenmount near Charley’s parents, after a music-filled funeral that included hymns written by his brother.

Originally published in the September 2013 issue of “Main Line Today.”

Buying the Race

Being rich doesn’t make somebody a natural at politics. Take, for instance, Joseph Newton Pew Jr. of Ardmore, an oil baron, shipbuilder and big-time Republican donor who missed his chance to be a kingmaker at the 1940 GOP convention in Philadelphia. The problem? At that critical moment, Pew was home in Lower Merion and, um, indisposed—too indisposed to accept a frantic phone call from the convention floor. “Over time, Joe’s ineptness acquired a comic quality,” wrote historian Paul B. Beers. “At the 1952 Republican convention, he stood up to cast his vote for General Douglas MacArthur. Absentmindedly, he announced his vote for ‘that great General of the Army, Ulysses S. Grant!’”

As a result, Pew and his politically active brothers at Sun Oil never did get much of what they wanted—specifically, the erasure of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Instead, the GOP went on to nominate moderate Dwight D. Eisenhower, who said of the “oil millionaires [and] occasional politician or businessman” still pressing to abolish Social Security: “Their number is negligible, and they are stupid.”

Joseph Newton Pew Jr.

Born in Pittsburgh, Pew was the son of Joseph Pew Sr. and his wife, Mary Anderson. Pew Sr. grew up on a Pennsylvania farm in Mercer County, about 40 miles east of Titusville, where the first American oil well was struck in 1859. He worked as a real estate broker, eventually invested in oil fields and began pumping natural gas. He was among the first to see the utility of gas for heating and lighting in both private homes and industry. Pew Sr. became a millionaire after the Spindletop strike in Texas in 1901. Spindletop was the first Gulf Coast oil field and was immensely rich. The oil it produced, however, could not be sold on the heavily populated East Coast, then in the grip of a monopoly by John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil. The solution? Pew’s Sun Oil Co. shipped the oil to Philadelphia—specifically, Marcus Hook, where the company built an 82-acre refinery. The refinery’s products were then sold in Europe.

Pew Jr. attended Cornell University, where he was on the track team and earned a degree in mechanical engineering in 1908. He then promptly joined Sun Oil, where his first accomplishment was persuading Dad to lay the first long-distance pipelines from Marcus Hook to distribution points in Ohio, New York and New Jersey. By then, Standard Oil’s monopoly was under attack, and young Pew saw potential.

The company’s foresight was rewarded in 1911, when a decision of the U.S. Supreme Court finally broke up Standard under the Sherman Antitrust Act. It was a formative moment in the development of the Pew brothers’ conservative political views. “It reinforced their conviction that industry thrives best when markets and competition are free,” wrote one historian. Pew Sr. had died in 1912. So, only four years after leaving Cornell, Pew Jr. found himself vice president of Sun Oil. His brother, J. Howard Pew, became president. In 1916, on the eve of World War I, Sun Oil expanded into shipbuilding, and Joseph Pew became president of the new entity, Sun Shipbuilding.

During the 1920s, Sun Shipbuilding became a major yard, producing tankers for competitors and Sun’s own needs. By 1941, it had eight slipways and, during World War II, added another 20, on which it produced more than 250 ships for the U.S. Maritime Commission.

Pew political activism dated to the early years of the Roosevelt administration. Both brothers had initially supported FDR but, repelled by New Deal policies that included price-fixing and support for organized labor, soon retreated to their native, ardent Republicanism.

The Pews were proudly paternal and, therefore, were offended at the very idea of organized labor. The company had anticipated and prepared for the stock-market crashes of the 1930s. During the Depression, Sun never laid off an employee or even cut salaries. The Pews were proud of that and didn’t want outsiders dictating their relations with their workers.

By 1934, Democrats in Pennsylvania controlled nearly every political office. In the Pews’ home state, it was unnerving. But what most galvanized Pew was the New Deal’s Petroleum Code, an agreement written by industry representatives to shore up falling gas prices and set production quotas. It was all price-fixing, declared Pew.

In 1936, he helped fund a national PR campaign against Roosevelt. To provide the Pennsylvania GOP with a suitable headquarters, Pew bought the Harrisburg Club and turned it over to the party rent-free.

Sometimes, Pew didn’t grasp that politics involved more than just writing checks. In Philadelphia, he picked a candidate, put up $200,000 for the race, and then went on vacation. When he got back, Pew was surprised to discover that his candidate had been scared out of the race with threats like: “Before I get through, I’ll take all the oil out of Pew—pew!”

Despite the Pews’ efforts, Roosevelt trounced GOP candidate Alf Landon, winning 60 percent of the vote and 46 states. In 1938, determined to take the governor’s office back for the Republicans, Pew put $250,000 into the campaign of Arthur James, a Superior Court judge who promised to “make a bonfire of all the laws passed by the (Democratic) 1937 legislature.” James won, and Republicans also recaptured both houses of the legislature, a majority of the congressional delegation, and both seats in the U.S. Senate. It was hugely encouraging. So, naturally, Pew was out for bear in 1940.

His preferred candidate that year was Robert Taft, a conservative U.S. senator from Ohio. The favored candidate, however, was Wendell Willkie, a lawyer and corporate executive with positions considerably more liberal. Pew’s “Stop Willkie” plan involved committing Pennsylvania’s delegates to vote for Governor James, the state’s “favorite son.” If Taft supporters could prevent Willkie from being nominated on the first ballot, the convention might lose interest and look for an alternative.

It took six ballots, though the movement toward Willkie had been apparent on the fifth. Politicians want to be on the winning side, so it made no sense to stick with other candidates too long. “The Pew delegates at the Philadelphia convention needed their boss’s order to switch votes on the fifth ballot, but Joe Pew couldn’t be reached,” wrote Beers. “His butler at Ardmore wouldn’t disturb the master in his bath.”

On the sixth ballot, Willkie won Missouri 26-4, New Jersey 32-0 and New York 78-7. Ohio stayed with Taft 52-0, but Oklahoma and Oregon went for Willkie. Pennsylvania was Taft’s last chance of stopping a stampede. But, with still no word from Ardmore, Pennsylvania passed. It fell to West Virginia to put Willkie over the top.

Too bad, Joe.

Originally published in the October 2017 issue of “Main Line Today.”

Scene From a Marriage

Some women can’t be satisfied. Consider Lucile Polk Carter of Bryn Mawr, whose husband got her and their two children safely into a lifeboat when the Titanic was sinking beneath them in 1912. Grateful? Not much. Lucile subsequently divorced William E. Carter, whose crime seems to have been that he survived, too.

Carter was the grandson of coal baron William T. Carter, who opened a mine in Luzerne County during the Civil War and got so rich on anthracite that, well, his bedroom furniture is now in the Pennsylvania Museum of Art. But the younger Carter spent little time in the mines. Before boarding the Titanic on April 10, the Carters had spent the winter in England’s Melton Mowbray district, a traditional center of fox hunting and high society. A “sportsman” who spent most of his time chasing foxes and playing polo, Carter was a regular at the Germantown and Merion cricket clubs and a familiar face in Newport, Rhode Island, where the social elite spent its summers.

Lucile was of a Baltimore family that had also produced James K. Polk, the 11th president of the United States. She and Carter married in 1897 and lived at Bryn Mawr in a mansion where a daughter and son were born in 1898 and 1900. Carter was also taking home a new 25-horsepower French Renault automobile, which was disassembled, crated and loaded in the Titanic’s hold. Eighty-five years later, in director James Cameron’s film version of the story, the Renault was shown fully assembled so that stars Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio could steam up its windows. Also along for the ride were Carter’s polo ponies and the family servants.

Wihout comment, Captain Edward Smith handed White Star director J. Bruce Ismay a fresh message warning of ice ahead. Ismay put the message in his pocket.

They did not lack company. When the Titanic steamed west, it carried some of the Carters’ closest acquaintances. Among them were John B. Thayer, 49, of Haverford, a vice president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, and George D. Widener, 50, of Elkins Park, heir to probably the largest fortune in Philadelphia and a member of the board of Fidelity Trust bank. Thayer, his wife and son had spent the previous two weeks as guests of the U.S. consul general in Berlin. The Wideners had been guests at the Ritz Hotel in Paris, which Harry, a 27-year-old book collector, had scoured for rare volumes.

On the afternoon of April 14, George Widener and his wife were seen standing on the promenade deck talking with J. Bruce Ismay, managing director of White Star, when Captain Edward Smith passed on his way aft. Without comment, Smith handed Ismay a fresh message from the liner Baltic, warning of ice ahead. Ismay put the message in his pocket.

That evening, in Captain Smith’s honor, the Wideners hosted a dinner party also attended by the Thayers, the Carters and Major Archibald Butt, a military adviser to President Theodore Roosevelt. Shortly before 9 p.m., Smith excused himself and headed for the bridge. After the women retired, the men sat in the smoking room to talk. “No one had any thought of danger,” Carter told the Washington Times five days later.

The men were still talking at 11:40 p.m. when the ship struck the iceberg. After assessing the situation, Carter walked to his family’s cabins. That’s where accounts diverge. Carter later claimed that he told his wife to wake the children, dress warmly and accompany him to the lifeboat stations. What Lucile later said in her divorce application was this: “When the Titanic struck, my husband came to our stateroom and said, ‘Get up and dress yourself and the children.’ I never saw him again until I arrived at the Carpathia at 8 o’clock the next morning, when I saw him leaning on the rail.”

Most accounts of the sinking agree that Titanic passengers were initially reluctant to enter lifeboats. It was warm and bright and dry in the cabins, and cold and dark and wet out on the sea. So even though Lucile and the children were probably dressed and topside by midnight or so, they and other passengers dawdled, ignoring the crew’s urgings as minutes ticked away. Lifeboat #4, with Lucile and the two children aboard, did not finally depart the Titanic until 1:55 a.m. The Titanic sank at 2:20 a.m.

Carter was probably unaware of this. Lifeboat #4 was on the port side of the ship, and the crew loading it—to facilitate the women-and-children-first rule—had ordered all men to the starboard side. Having delivered his family to the lifeboats, Carter had no choice but to seek safety on his own.

In such a situation, what does one do? Carter did what society folks usually do: He huddled with his friends to talk it over. Fortunes are not made or kept by acting rashly. He asked Harry Widener whether the young book-lover was going to try for a lifeboat.

Widener dismissed the notion. “I think I’ll stick to the big ship, Billy, and take a chance,” is how Carter later quoted him. The story conflicts with a legend among Titanic buffs that Harry missed a lifeboat when he ran to his cabin to retrieve a rare 1598 copy of Bacon’s Essays.

By about 2 a.m., all the regular lifeboats were gone. Carter was watching the crew unlash and load women into two collapsible lifeboats.

Order was breaking down. A crowd of desperate men tried to push their way into Collapsible C and two dining room stewards actually jumped in from a deck above. At this point, purser Herbert McElroy fired his pistol in the air. The crowd drew back. The stewards were thrown out. Loading continued until there were no more women and children in the vicinity. As the boat was released for lowering, Carter and another man stepped in. The other man was Ismay.

To many, it was all rather shameful. First, there was the problem that Carter survived at all. In 1912, male gallantry was highly and widely valued. “William’s big mistake was ending up as a live husband rather than a dead hero,” said Titanic scholar Robert Godfrey. “This didn’t go down well in the social circles that Lucile moved in.”

Another problem was Ismay. Despite his denials, rumors had it that he urged Smith to ignore ice warnings in the hope of setting a speed record. That would’ve made Ismay responsible for the wreck and his survival particularly shameful. Another problem: The Carpathia picked up Carter first. So he was safe aboard the rescue ship when Lifeboat #4 carrying Lucile and the children was brought alongside. And then he had the bad taste to lean over the railing and say to his wife that he’d had “a jolly good breakfast and was never sure she would make it.”

Complicating things further was that Lucile behaved well by the standards of the time. She’d pulled an oar. She’d not gotten hysterical. For a man, this would have been nothing much. For a woman, it was enough for the papers to call her a heroine.

Combined, it all made William Carter look like a coward. When the New York Times drily reported that the Carters, “the only Philadelphia family on the Titanic to be rescued without the loss of a member, show few efforts of their experience,” the condescension was apparent. Lucile endured the snubbing for 18 months, then filed for divorce. Her accusations regarding the sinking were sealed by the court but leaked to the press, causing a sensation. She remarried four months after the final decree and went to live near Pottstown.

William Carter, for his part, seems to have carried the stigma for the rest of his life. He never remarried. But he was alive, free to play polo and free of Lucile. From his perspective, the sinking of the Titanic might be said to have worked out OK.

Originally published in the April 2006 issue of “Main Line Today.”

Related: Explore the History Behind the Main Line’s Hidden Architectural Gems