By August Bernadicou (with additional text and research by Chris Coats) | NEW YORK – Many enduring symbols that establish an instant understanding and define a diverse community are intrinsically linked with controversy, confusion, and ill-informed backstories dictated by vested interests and those who told the story loudest. The LGBTQ rainbow flag is no different.

While it was the work of many, the people who deserve credit the most have been minimized if not erased. Gilbert Baker, the self-titled “Creator,” screamed the story and now has a powerful estate behind his legacy. Before his death in 2017, Baker established himself as the complete authority on the LGBTQ rainbow flag. It was his story which he lived and became.

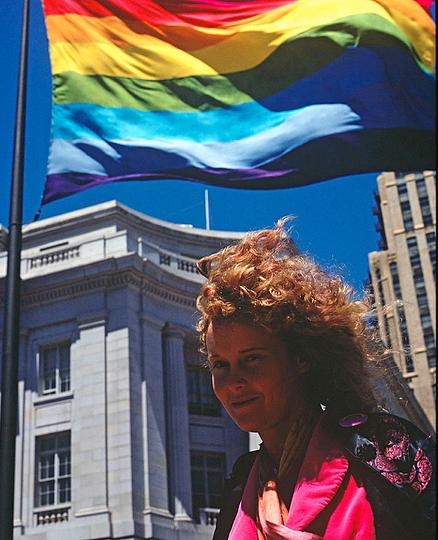

While there are disputed accounts on the flag’s origins, one thing that is not disputed is that the LGBTQ rainbow flag was born in San Francisco and made for the Gay Freedom Day Parade on June 25, 1978.

For all of human history, rainbows have mystified and inspired. A greeting of light and serenity after the darkness and chaos of a storm. They have symbolized hope, peace, and the mysteries of existence. For a moment, we can see the invisible structure, the “body” of light, made visible. A secret revealed, then hidden again.

Though it may seem like a modern phenomenon, rainbow flags have waved throughout history. Their origin can be traced to at least the 15th Century. The German theologian, Thomas Müntzer, used a rainbow flag for his reformist preachings. In the 18th Century, the English-American revolutionary and author, Thomas Paine, advocated adopting the rainbow flag as a universal symbol for identifying neutral ships at sea.

Rainbow flags were flown by Buddhists in Sri Lanka in the late 19th Century as a unifying emblem of their faith. They also represent the Peruvian city of Cusco, are flown by Indians on January 31st to commemorate the passing of the spiritual leader Meher Baba, and since 1961, have represented members of international peace movements.

Now, the rainbow flag has become the symbol for the LGBTQ community, a community of different colors, backgrounds, and orientations united together, bringing light and joy to the world. A forever symbol of where they started, where they have come, and where they need to go. When many LGBTQ people see a rainbow flag flowing in the wind, they know they are safe and free.

While the upper class and tech interests rule the city now, in the 1960s and 70s, San Francisco was a wonderland for low and no-income artists. The counterculture’s mecca. By the mid-1970s, the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood that had once been a psychedelic playground of hippie art, culture, and music had fallen into disarray. Hard, dangerous drugs like heroin had replaced mind-expanding psychedelics. Young queers and artists needed a new home, and they found it in the Castro.

Lee Mentley (1948-2020) arrived in San Francisco in 1972 and quickly fell in with the oddball artist and performers in the Castro neighborhood, donning flamboyant, gender-fucked clothes, performing avant-garde theater, and creating their own clubhouses. He was on the Pride Planning Committee in 1978 and ran the Top Floor Gallery on the top floor of 330 Grove, which served as an early Gay Center in San Francisco.

Lynn Segerblom (Faerie Argyle Rainbow) was originally from the North Shore of Hawaii and moved to San Francisco where she attended art school at the Academy of Art. Her life changed when she found a new passion in tie-dye and rainbows in the early 1970s. Entrenched in the free-loving technicolor world of San Francisco, in 1976, Lynn legally changed her name to Faerie Argyle Rainbow. She joined the Angels of Light, a “free” performance art troupe where the members had to return to an alternative, hippie lifestyle and deny credit for their work.

Shortly after the original rainbow flags were flown for the last time, both Lynn and Lee moved out of San Francisco. Lee moved to Hawaii and Lynn moved to Japan. When they returned, they were shocked to see how their contribution to history was becoming a universal symbol. They remain passionate about defending their legacies and giving a voice to the mute.

——–

LEE MENTLEY: “One day in 1978, Lynn came to 330 Grove with a couple of her friends, James McNamara and Robert Guttman, and said we should make rainbow flags for Gay Day to brighten up San Francisco City Hall and Civic Center because it’s all gray and cold in June. We thought that it sounded like a great idea.”

To get over the first hurdle, money, the young artists went to Harvey Milk, the first openly gay elected official in the history of San Francisco, California, for help.

LEE: “There was no actual funding for it. We contacted Harvey Milk and another supervisor, and they asked the city if we could get a little funding. They found some leftover funds from the previous year’s hotel tax, and we got $1,000.”

LYNN SEGERBLOM: “I remember having a meeting where I presented the idea of making rainbow flags. I had some sketches. At that meeting, there was just a handful of us there, and I remember, and even my friend assured me, that Gilbert Baker was not at that meeting. I don’t know where he was, I didn’t keep track of him, but he was not at the meeting where I suggested rainbow flags. We decided, yes, rainbow flags sounded great.”

The committee approved the rainbow imagery and made the decision to make two massive 40’ x 60’ foot rainbow flags to be flown at the Civic Center along with 18 smaller rainbow flags designed by different, local artists, to line the reflecting pool putting rainbows into the grey sky.

For the two large flags, one would be an eight-color rainbow starting with pink and including turquoise and indigo in place of blue, and the other a re-envisioning of the American flag with rainbow stripes which became known as Faerie’s flag.

——

Gilbert Baker’s name on his memoir, Rainbow Warrior, it says “CREATOR OF THE RAINBOW FLAG,” leaving little debate that Gilbert claimed full ownership for the concept and design of the legendary symbol. He never denied Lynn or James MacNamara’s involvement in the flags’ construction and speaks briefly and fondly of them and their talents in that same book.

LEE: “We didn’t need one person saving our ass, and it certainly wouldn’t have been Gilbert Baker. He was no Betsy Ross. He was a very good promoter, and I give him all the credit in the world for making the rainbow flag go international. He did a great service, and he was a very talented, creative man, but he could never have done all of the work by himself; no one could have.

We never considered ownership. There was never this big ownership debate until Gilbert started it. Because AIDS hit us so fast after this, most of our leadership either went into HIV activism or died.”

LYNN: “The story is that a white gay man did all of this by himself, but, in fact, that is not true at all. He just promoted it. For that, though, he should be given great love.”

————

Making the two original rainbow flags was no easy feat. With a limited budget and limited resources, the group had to improvise and figure it out as they went along. While Lynn had dabbled in flags before, a project of this scope and importance was far beyond her comfort zone.

LEE: “The community donated the sewing machines we used. We asked people at the Center if anyone would like to volunteer. All sorts of people from all over the country helped us with the flags, over 100 people, which, to me, is an amazing story. That’s where it came from. It came from regular artists who wanted to have fun and make something pretty for gay people.”

LYNN: “The Rainbows Flags were hand-dyed cotton and eight colors. I made two different types. The one with just the stripes and then the American flag one, which I designed myself. There was a group of us that made them, James McNamara, Gilbert Baker, and myself. Originally they were my designs. I was a dyer by trade, and I had a dying studio at the Gay Community Center at 330 Grove Street.”

LEE: “People would come and help as long as they could. Then, somebody else would come and help as long as they could. We opened up the second floor of 330 Grove to people who came to be in the Parade and march. People came in and made posters, banners and did art stuff.”

LYNN: “We made the flags on the roof because there was a drain up there. There was a wooden ladder that led up to the roof. The hot water had to be carried up to the roof because we didn’t have hot water up there. We heated it up on the stove in pots. We put the hot water in trash cans on the roof.”

LEE: “We had trash cans and two by fours, and we had to keep agitating the fabrics in the dye. Since they were in hot water, they had to be poked and agitated for hours.”

LYNN: “We had to constantly move the fabric in the dye, so the dye penetrated the fibers that weren’t clamped tight. We had to make sure there would be blue, and it wouldn’t just be white on white or white with a very murky, pale blue.

After they were washed and dyed, they went through the washer and dryer. Then, we ironed them. If the fabric stays out too long, once you take it out of the water, if it sits on itself even for just a few minutes, it starts to make shapes.”

—-

LEE: “Lynn’s flag, the new American flag, was a similar rainbow, but it had stars in the corner. I have photographs of that flag flying at gay events in San Francisco at City Hall and Oakland.”

LYNN: “I always liked the American flag. I thought, oh, wouldn’t that be nice? I knew with some luck I could make it.”

LEE: “I thought the one with the stars was more interesting because it symbolized a new flag for the United States.”

LYNN: “For my American flag, I decided to flip the order of the colors, so pink was at the bottom and purple was at the top in an eight-color spectrum. That was intentional. I wanted them to be different.

I made the stars with wood blocks and clamps. I got the white fabric and washed it, and folded it a different way. When I was making it, it looked like a big sandwich. The bread would be the woodblocks, and the fabric was in between. We immersed the whole flag in dye and swished it around. I wasn’t sure if it would come out right because it was the first time I did that fold. I was lucky. It worked.

I sewed lamé stars into one stripe with leftover stars from my Angels of Light costumes. On one side of the blue stripe, there was a star with silver lamé, and on the other side, there was a star with gold lamé.

I got all these ideas because I worked with these mediums on a daily basis: paint, dye, fabric, and glitter.”

—

LEE: “We worked for weeks dying fabric, shrinking fabric, and sewing fabric.”

LYNN: “We worked on them for seven weeks. I was worried that we weren’t going to finish on time. We worked hard and long hours. Towards the end, we decided we didn’t have time to go to the laundromat, so we started rinsing them on the roof and wringing them dry. We also ran out of quarters. We draped them off of the Top Floor Gallery’s rafters, and they drip-dried. They looked great. They were beautiful.”

Until that day, the pink triangle, used by the Nazis to label homosexuals in their genocidal campaign, was the most commonly used symbol for the LGBTQ movement, a symbol in solidarity with our fallen ancestors. But the triangle came from a place of trauma, it was a reminder of the storm while the rainbow was the hope that came after. The promise of brighter days ahead.

On that day in June 1978, it felt as if the rainbow had always been a symbol for the LGBTQ community, it just hadn’t revealed itself yet.

LEE: “We went out, flew the flags, and blew everybody’s fucking minds. People were blown away. The flags were so beautiful. They were waving warriors. The biggest ones were 40’ by 60’ feet. The Parade marched through the flags to get to Civic Center. We instantly proclaimed that this was our symbol. It wasn’t planned. It was organic.”

LYNN: “It was just what I wanted: a touch of magic, a touch of glitter, and a little bit of Angels of Light.”

LEE: “We weren’t creating this huge symbol. We were decorating Civic Center. We weren’t thinking of marketing our entire futures. It was an art project.”

LYNN: “We looked at the rainbow flags as a work of art, and we wanted them to be beautiful and unique. After the Gay Parade, the flags were a big hit. People loved them. Everybody loved them.”

—-

In the pre-technology world, people and property could just disappear. There were no surveillance cameras. Lynn didn’t even have a phone.

Even though no one could have known the flag would become an eternal symbol for a worldwide community, it was clear even then that they were a piece of history to be coveted.

In his memoir, Baker hypothesizes that the Rainbow American flag was stolen shortly after it was hung up on the front of the Gay Community Center for Gay Freedom Day in 1979. He suggests it might have been a construction crew working on the new symphony across the street and in a homophobic act, stole the flag and buried it in cement.

LEE: “Later in 1979 or 1980, you can find it somewhere in the minutes for a Pride Foundation meeting, Gilbert came to us and asked to borrow the two large flags, and we agreed. We never saw them again.”

LYNN: “I went to work one day at 330 Grove, and Gilbert came in and said that the two 40’ by 60’ flags had been stolen.”

Images published in the San Francisco Chronicle, videos of the march, and other widely distributed photographs only add to the mystery. They show both the classic rainbow flag of eight stripes and the American revision flying at the Civic Center on June 24, 1979 and not at the Gay Community Center.

As for the original eight-stripe flag, there are even fewer answers. In his memoir, Baker says that while they were taking down the flags from Civic Center, he was hit on the head on knocked out. “When I came to on the muddy ground,” he says “I saw people all around me hitting each other and screaming obscenities. They were fighting over the rainbow flags, pulling on them like a game of tug-of-war, tearing them.”

LYNN: “It would have taken more than one person to carry the flags. It took three people to carry one folded-up flag for the Parade, and we needed a van. They weighed a lot, and 330 Grove did not have an elevator. Whoever stole them had help—one person could not do it on their own.”

—-

LYNN: “Before the rainbow flag missing, Gilbert came to one of my workshops. He wanted to watch me dying fabric all day and see how I did everything.

I was like, oh yeah, I’ll show you, come in.

I said, here, put some gloves on and do it with me.

He was like, oh, no, no, I don’t want to get my hands dirty.

He was only trying to figure out how I did the dying.”

—-

LEE: “Gilbert went to these places like MoMa and told them these outrageous stories about how he made the rainbow flag all by himself. He said this about the flag he donated. When you look at it, you can tell that it was bought at a craft fair. It flat out wasn’t one of our flags. It was polyester.”

LYNN: “It was polyester, it wasn’t the same size, and it wasn’t hand-dyed. My flags were different. The rainbow flag at MoMa was a beautiful flag inside a frame, but it wasn’t an original, not from 1978, not even a piece from 1978. I was hoping, oh, my God, maybe this is a piece of it.”

LEE: “It wasn’t even the original colors. MoMa said they were original flags, but they weren’t. It was a commercially produced rainbow flag with a primary color rainbow. The plaque cited Gilbert donating it as an original flag.”

—-

LYNN: “I read online that Gilbert Baker said he named me “Faerie Argyle Rainbow,” a complete lie. Bethany the Princess of Argyle named me. I chose the name Rainbow because I was known as a rainbow artist.”

LEE: “Even Lynn’s driver’s license said her name was “Faerie Argyle Rainbow.””

LYNN: “In 1976, I filled out a form at the DMV, and my name became Faerie Argyle Rainbow. Back then, they didn’t ask you for a birth certificate. The employee just said, “This is your name now,” and gave me a driver’s license that said Faerie Argyle Rainbow.

It all sounds crazy now, but back then, it wasn’t.”

—–

LEE: “I had my arguments and fights with Gilbert Baker because he claims he came up with the rainbow flag. If you go through all of his different interviews, you see that his story changes over and over and over again. He even said Harvey Milk came to him and asked him to create a symbol for the movement. No—I read that, and no such thing happened.”

LYNN: “Just look at his interviews. His takes on what the colors in the rainbow flag mean are all in his head. The rainbow represents everyone, no matter what gender or race you are; that’s how I looked at it. Rainbows are in nature and beautiful. People love them, and I love them. I knew they would be great color healing.

Gilbert assigning meaning to each color is ridiculous. I think anyone could make up what each color means. If I wanted to, I could do the same. It wasn’t what I was thinking. I was thinking that rainbows encompass everybody, the whole group, unity.”

LEE: “I have tried to convince people that the rainbow flags were made with tax-payer dollars. We made them as a non-profit.

Not even Gilbert owns them. I have always thought that anyone who sells anything rainbow should give a portion of the profits to homeless gay youth. We need to take care of our own kind because no one does. The whole concept of taking care of gay people has disappeared.”

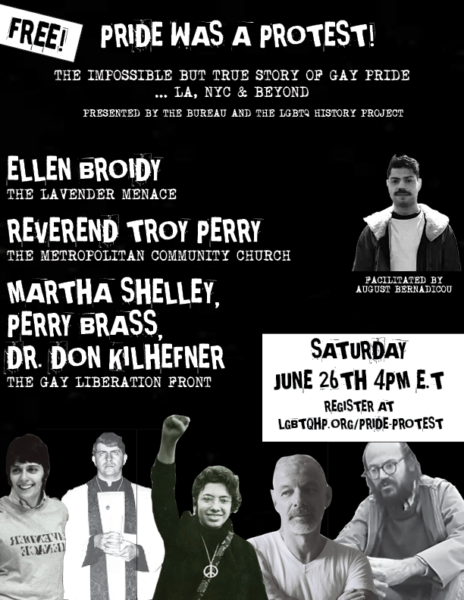

August Bernadicou is a 27-year-old gay historian and the President of the LGBTQ History Project Inc. Chris Coats is an editor and producer.

Together, they produce the QueerCore Podcast and will shortly be releasing an episode that is the definitive story on the rainbow flag featuring Lee Mentley, Lynn Segerblom, and Adrian Brooks.

August Bernadicou is presenting a Pride event in NYC this year that all folks are cordially invited to attend- its virtual;

Here is the link for the event: https://www.lgbtqhp.org/pride-protest